Per il primo post del 2014 dedicato all’ interpretazione liederistica, ho scelto uno dei capolavori assoluti della letteratura vocale di Johannes Brahms. Si tratta della “Sapphische Ode”, quarto numero del ciclo Fünf Lieder für eine tiefe Singstimme und Klavier op. 94, composto nel 1884, poco dopo la Terza Sinfonia e pubblicato dall’ editore Simrock di Berlino nel dicembre dello stesso anno. La prima esecuzione della “Sapphische Ode” avvenne nell’ ambito di una Liederabend viennese del 9 gennaio 1885 ad opera di Gustav Walter (1834 – 1910), tenore boemo che fu per più di trent’ anni il massimo divo della Wiener Hofoper, dove interpretò sia il repertorio italiano, soprattutto come rinomato specialista delle opere di Mozart e Verdi, che quello wagneriano, nel quale colse una delle sue più grandi affermazioni come Walther von Stolzing nella prima viennese dei Meistersinger, nel 1870. La “Sapphische Ode” è uno dei massimi esiti raggiunti da Brahms nel campo della liederistica, per la bellezza della linea melodica e il tono nobilissimo della linea del canto, sostenuta dagli accordi sincopati del pianoforte. Come ha scritto il musicologo francese José Bruyr, nella sua fondamentale monografia brahmsiana pubblicata nel 1977:

Se dovessimo scegliere un solo Lied di questa raccolta, ebbene, la scelta cadrebbe sulla celebre Ode saffica: questo per via di una speciale, tenace attenzione che ci tiene legati a quelle dodici battute: una melodia dall’essenza di rosa, il cui peso è quello di un petalo…

Ecco il testo di Hans Schmidt (1854 – 1923), poeta, pianista e compositore, che intrattenne stretti rapporti di collaborazione con Brahms e altre personalità prominenti dell’ entourage del musicista amburghese, come il violinista Joseph Joachim e il baritono Julius Stockhausen.

Rosen brach ich nachts mir am dunklen Hage;

Süßer hauchten Duft sie als je am Tage;

Doch verstreuten reich die bewegten Äste

Tau, der mich näßte.Auch der Küsse Duft mich wie nie berückte,

Die ich nachts vom Strauch deiner Lippen pflückte:

Doch auch dir, bewegt im Gemüt gleich jenen,

Tauten die Tränen.

Questa è la traduzione italiana, nella versione di Ferdinando Albeggiani

Rose ho colto, di notte, dal cespuglio oscuro;

più che di giorno esalavano profumo;

e i rami scossi sparsero rugiada,

e mi ritrovai tutta inzuppata.Anche il profumo dei baci mi ha sedotto

Che dal cespuglio delle tue labbra ho raccolto:

ed anche da te, nell’animo turbata,

più di una lacrima è caduta.

Passiamo adesso ai contributi critici, iniziando con questa breve ma esaustiva analisi, scritta dalla cantante Whitney Laine Westbrook come Senior Project per il conseguimento del Degree Bachelor of Arts.

Johannes Brahms (Hamburg, 1833-Vienna, 1897) created many splendid masterworks, one of them being his beloved “Sapphische Ode (Sapphic Ode),” the fourth song from his Lieder cycle Five Songs for Low Voice with Piano Accompaniment. In the summer of 1884, Brahms collaborated with poetic genius Hans Schmidt (1854-unknown) in order to birth this story surrounding a love like a rose that was so sweet and yet eventually died away, bringing tears of melancholy; it was in this season that Brahms would compose a love song to surpass any love song ever to have existed.

Johannes Brahms delved into music as a young teen playing piano in waterfront bars and brothels. Although noteworthy musical debuts were absent from Brahms’ life at the time, the quiet and reserved young man worked hard to make up for the life of poverty into which he was born. At the age of 20, Brahms left the brothels for a life touring with world-famous Hungarian violinist, Ede Reményi.

While on tour, Brahms was introduced to world-renown violinist Joseph Joachim, who later became his life-long friend; however, Joachim became more than just a friend to Brahms. Joachim recognized musical talent within the young pianist and, thus, sent Brahms to the house of Robert and Clara Schumann to study piano performance and composition. Brahms was received with excitement as the Schumanns also saw great talent within the young musician; this reception into the Schumann household was seen as the beginning of a tight bond between the Schumann family and Brahms. Between 1851-1896, Brahms went on to publish 31 volumes and 194 songs for the solo voice and piano, as well as duets, 2 songs with viola, and 121 arrangements of Germans folksongs. “Sapphische Ode” was one song that out amidst the plethora of Brahms’ creations. With singer Julius Stockhausen’ s “dark-toned voice” in mind to pair with the Lied’s subject matter, Brahms originally wrote the 3/2 metered piece in the key of D Major; however, simultaneously a version of the piece was published in F Major, allowing a higher voice to partake in the Sapphic ode. The piece was orchestrated to be sung with orchestra, but was also composed to accommodate a single voice with pianoforte accompaniment.

Brahms chose Hans Schmidt’ s poem titled “Gereimte sapphische Ode (Rhymed Sapphic Ode)” for its beautiful story which described a walk through a rose garden at night. A once-sweet memory of a love experienced brings tears of sorrow to the singer when recalling her lost love’s kiss. Schmidt titled his poem, after the female Greek lyric poet, Sappho, (c. 600 B.C.), who often used the same poetic form as Schmidt’ s poem. The structure of the poem is brought to life through Brahms’ placing of harmonies and melodic line which coincide with the lyrics. Tenderness is perceptible within the langsam song due to the absence of forte dynamic markings. During the majority of the love story, the singer’s voice does not exceed the boundaries between piano and mezzo piano. Although the story does surround the devastated songstress, the piano plays by itself as its own character. The piano can be seen as having two roles as it glides along in between the two stanzas: 1) to provide comfort to the singer’ s past lamentations and 2) to encourage the singer with happier thoughts that provoke another stanza filled with happier thoughts. As each stanza concludes, the harmony concludes on the tonic of F to provide closure to the last memory lived over for the last time.(estratto da Whitney Laine Westbrook, The Lied of Five German Composers, Degree Bachelor of Arts, Faculty of the Music Department of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, 2010)

Questo invece è uno studio più dettagliato, tratto dal blog del musicologo danese Kristoffer Brinch Kjeldby

The poem Sapphische Ode, written by German poet and composer Hans Schmidt (1854-1923) in 1881, was sent by the author to Johannes Brahms, a friend of Hans Schmidt. Brahms, then in his fifties, shortly thereafter composed a lied based upon the poem. The lied was published in December 1884 by Stefan N. Simrock in Berlin and was the fourth song in the collection Fünf Lieder für eine tiefe Singstimme und Klavier, op. 94.

The poem

The poem is written in ‘Sapphic stanza’ (an antique stanza named after Sappho of Lesbos) and is subtitled In Antiker Form. Being arcaic in form only, the poem describes how the narrator picked roses a night, overwhelmed by the sweet fragrance and moistened by dew:

Rosen brach ich nachts mir am dunklen Hage;

Süßer hauchten Duft sie als je am Tage;

Doch verstreuten reich die bewegten Äste

Tau, der mich näßte.The poem’ s second stanza parallels the nocturnal experience with the sweet kisses plucked from the lips of a beloved and comparing the dew to falling tears.

Auch der Küsse Duft mich wie nie berückte,

Die ich nachts vom Strauch deiner Lippen pflückte:

Doch auch dir, bewegt im Gemüt gleich jenen,

Tauten die Tränen.The poem is rhymed in a simple AABB pattern and there are many parallels in the lyric composition of the two stanzas, especially in the third and fourth verse as indicated with different colors above.

The music

The lied, composed in a strophic form, contains two musical nearly identical strophes. Each strophe, in accordance with the stanza of the poem, contains three verses of 11 syllables, followed by a short verse of 5 syllables, a structure that is closely reflected in the phrases of the song.

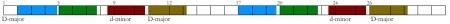

Brahms lied spans 30 measures and is written in D-major with modulations to d-minor. The overall time signature is 4/4 (with signature changes to 3/2), and the tempo is indicated as Ziemlich langsam (rather slow), with a vocal ambitus from a to d′. The formal layout, and the distribution of the 4 phrases/verses, can be illustrated as follows:

The lied begins with a single measure piano introduction: Syncopated D-major chords above a right hand melody in whole notes placed on first and third beat. The vocal melody starts out mostly in on-beat quarter notes, hence strengthen the syncopated character of the accompaniment. The first verse phrase (measure 2-4) moves within the notes of the D-major chord, starting from f#′, moving down through d′ down to a.[1] The phrase consists of two irregular parts, as the first three tones are is repeated in measure 3-4. The accompaniment as well as the vocal melody is set in a rather low range, avoiding voice crossing between the voice and the upper part piano. The phrase concludes in measure 4 with a simple cadenza to D-major.

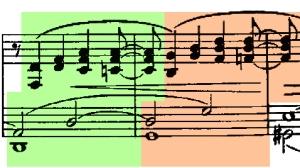

The second verse phrase (measure 5-7) preserve much of the melodic and rhythmic contour of the first verse phrase – but moves stepwise, not through, broken chords. This results in a phrase that spans a slightly narrower ambitus (a-g′). The right hand chords of the accompaniment, still in syncopated quarter notes, now venture into the range of the melody, playing along with the voice an eighth note behind from the actual vocal melody.The harmonies (set above a sustained D pedal point) moves downwards from the subdominant G-major, and reaches a repeated chromatic turn from C#-major to D-major, where C# serves as a tritone substitution for the dominant, while highlighting the expressive halftone step from c#′ to d′. The second line reaches its conclusion with a cadenza from the subdominant G-major through a dominant seven chord to D-major in measure 7.

Figure 1: Measure 5-7. The piano plays along with the vocal melody (red). The g# is swapped between the piano left and right hand, allowing Brahms to continue the stepwise left hand motion (green). The phrase is set above a d pedal point (blue).

After the second line concludes on f# in measure 7, the accompaniment moves up an octave while fading to pianissimo preparing for the third phrase. This third verse phrase starts from d′ (the vocals highest note) in measure 8, drastically expanding the vocal ambitus upwards, and intensifying the expressive character of the melody.

The third verse phrase closely matches the second phrase, transposed up a fifth, and starting on the third beat instead the first. This rhythmical displacement is “corrected” due to the change to meter in measure 9. But most important, the key changes via a D-dominant and a g-minor subdominant to d-minor in bar 9. This shift in tonal center is a followed by a expressive repeated movement from the secondary dominant E-major to d-minor, highlighting the chromatic movement from g#′ to a′ in the melody (parallel to measure 6). The phrase concludes with a modulation back to D-major, preparing for the short fourth verse phrase. The fourth phrase consists of a downward stepwise and embellished movement from f#′ to d′, and end with a cadenza to D-major in measure 13.The first stanza is followed by a short piano interlude (measure 13-16). The interlude is composed of three parts: The first two bars consist of a repeated chordal pattern returning to the broken chords of the first verse phrase, first over a D-major dominant, then over a G-major:

Figure 2: The first part of the piano interlude consists of two overlapping chordal pattern.

The last part of the interlude steps back down first through a E-major secondary dominant and the through a A-major dominant, preparing for the second stanza entry in measure 17.

The poem’s second stanza is musically identical to the first one – with a few exceptions: In the second part of second phrase, Brahms chooses to move the melody as well as the accompaniment up a bit (measure 21-22). The second part of the third phrase is on the other hand moved down a bit (measure 24-25), slightly changing the expressive balance between the two phrases.

Summary

Brahms employs a number of techniques to emphasize the nocturnal character of the poem: The syncopated left hand chords used throughout the piece adds a certain rhythmic ambiguity, combined with phrases of the accompaniment that often contrasts the phrases of the melody.

The combined rhythmic and phrasing ambiguity, coupled with the pedal points used in measure 4-9 and 21-24, gives the accompaniment a subtle character: chords gently moving above a unmovable soft ground.

This uncertainty is mirrored by the interplay between melody and piano, where the piano right hand, while mimicking the song, never actually ‘catching up’ with the song.

The accompaniment is rather uniform in character, keeping the same rhythmic figure throughout the piece. The third verse is the expressive highpoint of the both stanzas. This is achieved via a diminuendo to pianissimo, a change to staccato, a modulation to minor, and most importantly a sudden upwards expansion of the vocal range.

Except for the first verse phrase, the phrases a composed from embellished stepwise and mostly falling lines, a feature that also makes up a significant part of the accompaniment. The exceptions ( the first verse phrase and the piano interlude) uses simple arpeggios. This gives the song a rather simple melodic profile.

Nel suo celebre studio sull’ interpretazione liederistica, la grande Lotte Lehmann ci ha lasciato queste interessanti indicazioni esecutive.

This song is pervaded by the darkness and the mysterious beauty of a warm summer night. It should be sung floatingly, with a dark quality and deep emotion, but without sentimentality. Avoid a to slow tempo – this song should be moderato rather than slow. The marking “rather slowly” is in my opinion, more a warning not take the song too fast. Begin with a cello-like quality. Accent glowingly: “Süßer hauchten Duft sie als je am Tage”. “Doch verstreuten reich die bewegten Äste” should be sung with the utmost lightness, with a silvery and ethereal quality. Tie the word “Äste” over to “Tau” (in the way which I have explained in the Introduction, page 15). In the interlude (as throughout the whole song) the branches sway in the warm night wind. Take up the gentle rhythm with your body, follow it (very, very discretely) in your feeling, your expression… The first verse was a tender, compassionate description of nature, in the second verse your own individual experience flows your delighted observations. Sing “Auch der Küsse Duft mich wie nie berückte” very darkly and passionately and give much emphasis to the word “duft”, sing this with closed eyes, losing yourself in this enchanting remembrance… Sing “Die ich nachts vom Strauch deiner Lippen pflückte” with an impelling force. Yet you hesitate now – it is as if you see before you the face of your beloved, as you saw it on that night – pale, unreal, consumed by a passion so strong that it made her weep. Sing “doch auch dir, bewegt im Gemüt gleich jenen” very subtly, with restrained delight, lost in the happy memory. The marking in the song indicates crescendo and decrescendo at “Tauten”. I myself sing a crescendo with the first two tones and then go over into a subito pianissimo at the third tone. This of course is a matter of purely personal opinion but I have the feeling that the memory of those tears of delights is almost too much… , that you scarcely dare to relive this memory… That is why I make a subito pianissimo – but of course it is completely within the style of the Lied – perhaps even more “correct”, if I may say so – to go on in a full crescendo… Sing the final “Die Tränen” broadly with a soft swing. In the postlude feel yourself sinking into the glow of your overwhelming memories…

(Lotte Lehmann, More than Singing, originally published by Boosey and Hawkes, New York, 1945. Rist. da Dover Editions, 1985, II ed. 2012)

Passiamo adesso agli ascolti, iniziando con un omaggio a un’ artista vittima di un destino fra i più tragici. Ottilie Metzger-Lattermann (1878-1943) fu una delle massime cantanti di lingua tedesca nei primi decenni del secolo scroso. Prescelta da Gustav Mahler come solista nella prima esecuzione dell’ Ottava Sinfonia a München, si esibì ad Amburgo a fianco di Enrico Caruso e fu collaboratrice fissa di direttori come Leo Blech, Otto Klemperer e Bruno Walter. Perseguitata dai nazisti a causa delle sue origini ebree, fuggì nel 1939 in Belgio ma, quando i tedeschi invasero il paese, venne arrestata, nonostante il Kaiser Wilhelm II avesse scritto, dal suo esilio olandese, una lettera personale di intercessione in suo favore, e deportata ad Auschwitz dove morì probabilmente poco dopo il suo arrivo. Una lapide in sua memoria è stata posta nel Festspielpark di Bayreuth. L’ esecuzione della Metzger, registrata nel 1910, è un esempio probante di canto di altissima scuola. Il timbro autenticamente contraltile è messo in rilievo da una tecnica di altissimo livello e il fraseggio è davvero di classe eccelsa.

Abbiamo già avuto modo di fare esperienza, nei precedenti post di questa serie, riguardo alle superbe interpretazioni liederistiche di Alexander Kipnis (1891 – 1978) e anche in questa occasione vi ripropongo la voce del basso ucraino, in una registrazione Columbia del 1929.

Impressionante, come sempre, la densità e la ricchezza di armonici del timbro. Il canto, anche in questo caso grazie a una preparazione tecnica di livello superiore, ha la calma maestosità e il vigore di un grande fiume che scorre; l’ espressione colpisce per il tono solenne e ieratico del fraseggio.

Grace Bumbry (1937) fu allieva di Lotte Lehmann alla Music Academy di Santa Barbara, in California. “Die schwarze Venus”, come venne soprannominata dopo il suo sensazionale debutto a Bayreuth nel ruolo di Venus del Tannhäuser, è stata interprete liederistica di altissima classe. In questa registrazione del 1962, con l’ accompagnamento pianistico di Erik Werba, la cantante di St. Louis dimostra perfetta padronanza della pronuncia e un fraseggio sicuramente ispirato alle indicazioni della sua insegnante, che abbiamo pubblicato qui sopra. Ascoltate come la Bumbry realizza alla perfezione il decrescendo sulla parola “Tauten” suggerito dalla Lehmann nel suo studio.

Come ultimo ascolto, ho scelto una cantante di oggi. Ascoltiamo la versione del mezzosoprano Ingeborg Danz, nativa di Witten e oggi cinquantaduenne. Sebbene non appartenente al mondo dello star system, nonostante abbia lavorato con quasi tutti i massimi direttori del nostro tempo, la Danz è a mio avviso una delle migliori interpreti odierne nel campo della liederistica e della musica sacra, come ho avuto modo di constatare personalmente in diversi ascolto dal vivo. La sua versione del Lied, incisa insieme a Helmut Deutsch, è assolutamente esemplare per eleganza della linea vocale, legato di alta scuola e castigatezza di espressione.

Quattro versioni di eccellente livello, e anche in questo caso la scelta dipende soprattutto dal proprio gusto personale. Torneremo a parlare della liederistica di johannes Brahms nella prossima puntata di questo ciclo.