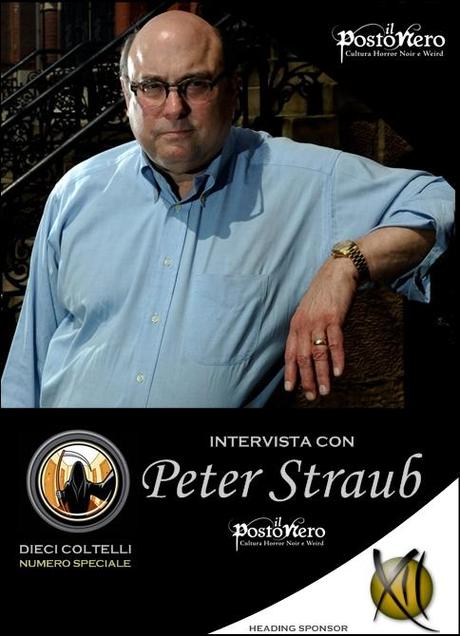

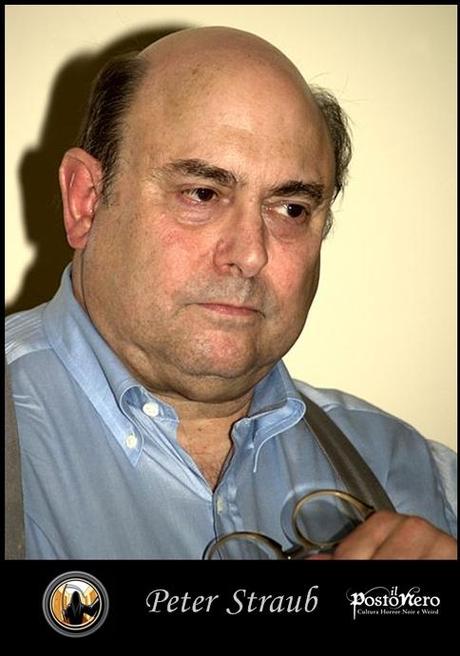

Ten Knives Interview with Peter Straub, horror legend:

Knife 1) Please name at least three contemporary authors who write generally better than you do and why.

[Peter Straub] This is a terrible, terrible question. I thought about naming three poets. I thought about skipping it altogether. I thought about saying, "Impossible, because three contemporaries who are better than I do not exist." However, although the third response is both honest and true, let me name: John Crowley, the best writer alive today, Elizabeth Hand, another completely wonderful writer. Certain mysterious and ecstatic moments in her Mortal Love resemble things I would do and have done, but hers have more beauty and urgency. David Plante, whose spiritual gravity I could never approach, much less equal.

Knife 2) Has ever something happened in your life that made you think of giving up writing?

[Peter Straub] No, nothing has ever made me think of giving up writing. Writing was never the problem, always the answer.

Knife 3) Which compromises did you have to accept for commercial reasons?

[Peter Straub] I realized that I would have to write books that were more accessible than not, and that each novel would have to have a real narrative climax. Of course these were excellent ideas, not compromises.

Knife 4) Is it very important to win literary prizes? Does it help to sell?

[Peter Straub] Prizes are wonderful to win, and they probably do help, in some exceedingly minor way, to sell books. Mainly, however, what they do is to make a lot of genre writers who have no hope of ever really being any good seriously, seriously envious. Because they actually write in the hope of winning those same (unattainable) prizes.

Knife 5) When you have no ideas for writing, how do you bring down yourself and whom do you phone to?

[Peter Straub] During fallow days, I drift around the house, watching DVDs, reading fiction, ordering rare books from catalogues, talking to the cat. I never phone anybody at all, except sometimes Gary K. Wolfe.

Knife 6) What do you think when you read your country's best seller rankings?

[Peter Straub] Hmm, I think, so this is what people are buying. Ouch, Grr. That's absurd. Will you please get serious? Oh, okay, I Ioved that book. Hey, I loved that one, too. Oh hell, THAT dim, dull-witted thing? Ugh grr. And so on.

Knife 7) What do you reproach to American publishing? What are its limits?

[Peter Straub] I do not reproach American publishing, except for their failure to publish many times more translations.

Knife 8) How many times have you refused to participate to a no-profit project?

[Peter Straub] Not often. I do refuse to participate in almost every project offered to me, though.

Knife 9) What did you do right after signing major book deal?

[Peter Straub] The first time? I floated around for a while, my feet well off the carpet, then bought some new bound journals and good pencils, and after that I wandered off and had a couple of drinks.

Knife 10) Whom to (or to what) would you throw a knife?

[Peter Straub] Throw a knife? I own seven or eight good knives, Bastides, mainly, and have no wish to throw one of them at anything or anyone. My life is pretty quiet. Please forgive me for taking this question literally.

And now, two special knives for Peter Straub::

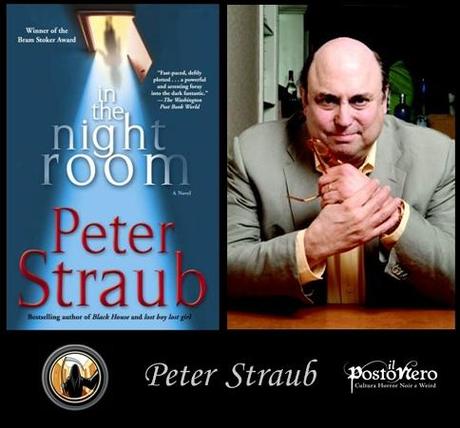

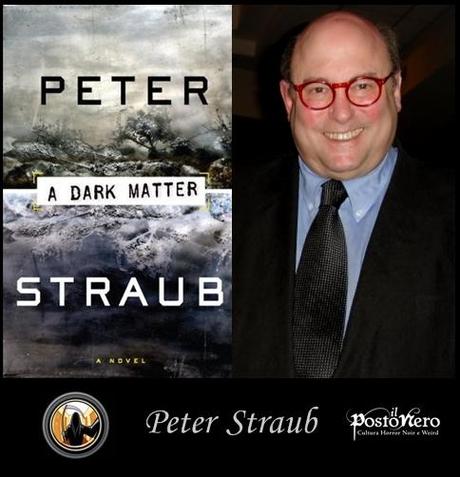

Knife 11) Three reasons to read your latest book: A Dark Matter

[Peter Straub] It is unlike anything I've ever written before. It is unlike anything you have ever read before, probably. A lot of smart people really liked it: Dan Chaon, Brian Evenson, Lorrie Moore, Bradford Morrow.

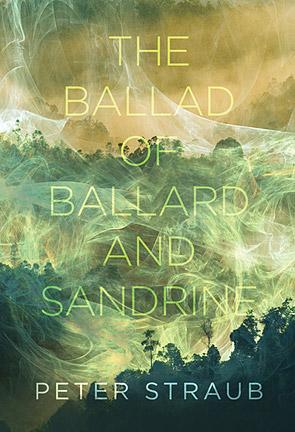

Knife 12) Where will take us the Amazon River of your latest novella The Ballad of Ballard and Sandrine?

[Peter Straub] My Amazon, only tangentially related to the actual river in South America, drags its readers down a long, long staircase, roughs them up, subjects them to perverted sex, and finally boots them out onto the street, their eyes full of tears and their heads full of conflicting visions. Something has happened, out there on that strange yacht, but you understand that it is awfully difficult to define.

Leggi l'intervista in Italiano

Biography:Peter Straub was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin on 2 March, 1943, the first of three sons of a salesman and a nurse. The salesman wanted him to become an athlete, the nurse thought he would do well as either a doctor or a Lutheran minister, but all he wanted to do was to learn to read. When kindergarten turned out to be a stupefyingly banal disappointment devoted to cutting animal shapes out of heavy colored paper, he took matters into his own hands and taught himself to read by memorizing his comic books and reciting them over and over to other neighborhood children on the front steps until he could recognize the words. Therefore, when he finally got to first grade to find everyone else laboring over the imbecile adventures of Dick, Jane and Spot (“See Spot run. See, see, see,”), he ransacked the library in search of pirates, soldiers, detectives, spies, criminals, and other colorful souls, Soon he had earned a reputation as an ace storyteller, in demand around campfires and in back yards on summer evenings.

This career as the John Buchan to the first grade was interrupted by a collision between himself and an automobile which resulted in a classic near-death experience, many broken bones, surgical operations, a year out of school, a lengthy tenure in a wheelchair, and certain emotional quirks. Once back on his feet, he quickly acquired a severe stutter which plagued him into his twenties and now and then still puts in a nostalgic appearance, usually to the amusement of telephone operators and shop clerks. Because he had learned prematurely that the world was dangerous, he was jumpy, restless, hugely garrulous in spite of his stutter, physically uncomfortable and, at least until he began writing horror three decades later, prone to nightmares. Books took him out of himself, so he read even more than earlier, a youthful habit immeasurably valuable to any writer. And his storytelling, for in spite of everything he was still a sociable child with a lot of friends, took a turn toward the dark and the garish, toward the ghoulish and the violent. He found his first “effect” when he discovered that he could make this kind of thing funny.

As if scripted, the rest of life followed. He went on scholarship to Milwaukee Country Day School and was the darling of his English teachers. He discovered Thomas Wolfe and Jack Kerouac, patron saints of wounded and self-conscious adolescence, and also, blessedly, jazz music, which spoke of utterance beyond any constraint: passion and liberation in the form of speech on the far side of the verbal border. The alto saxophone player Paul Desmond, speaking in the voice of a witty and inspired angel, epitomized ideal expressiveness, Our boy still had no idea why inspired speech spoke best when it spoke in code, the simultaneous terror and ecstasy of his ancient trauma, as well as its lifelong (so far, anyhow) legacy of anger, being so deeply embedded in the self as to be imperceptible, Did he behave badly, now and then? Did he wish to shock, annoy, disturb, and provoke? Are you kidding? Did he also wish to excel, to keep panic and uncertainty at arm's length by good old main force effort? Make a guess. So here we have a pure but unsteady case of denial happily able to maintain itself through merciless effort. Booted along by invisible fears and horrors, this fellow was rewarded by wonderful grades and a vague sense of a mysterious but transcendent wholeness available through expression. He went to the University of Wisconsin and, after opening his eyes to the various joys of Henry James, William Carlos Williams, and the Texas blues-rocker Steve Miller, a great & joyous character who lived across the street, passed through essentially unchanged to emerge in 1965 with an honors degree in English, then an MA at Columbia a year later. He thought actual writing was probably beyond him even though actual writing was probably what he was best at - down crammed he many and many a book, stirred by some, dutiful to the claims of others, and, more important than any of this, educated by the writerly example of his dear, eternal friend, the poet Ann Lauterbach.

Stuffed with books and opinions about books but out of money, he married his beloved, Susan, took a job teaching English at his old school, now renamed University School of Milwaukee, and enjoyed a minor but temporary success as Mr. Chips-cum-jalapenos, largely due to the absolute freedom given him by the administration and his affection for his students, who faithfully followed him as he struck matches and led them into caves named Lawrence, Forster, Brontë, Thackeray, etc., etc. On his off-hours, he fell in love with poetry, especially John Ashbery's poetry, and wrote imitations of same. Three years later, fearing to turn into a spiritless & chalk-stained drudge, he went to Dublin, Ireland, to work on a Ph.D., secretly (a secret even to him) to start writing seriously.

Dublin, 1969-1972. His dissertation, a mess, devolved. He published poems in poetry places, did readings with new friend Thomas Tessier who was writing plays and poems, published two small books of poetry, Ishmael and Open Air, and finally surrendered to psychic necessity and wrote a novel, not at all a good novel, called Marriages, accepted by the first publisher to whom it was, heart in mouth, sent. He moved to the larger world of London.

London, 1972-1979, Ann Lauterbach lived on the other side of Belsize Square; Thomas Tessier soon materialized, magnificently, as the Managing Director of a publishing house. He wrote & wrote & sometime in 1974, in desperation and despair first gathered up his ancient fears and turned them into fiction & by doing so saved his life. He and Ann talked about poetry, the mysteries of everyday life and everything else; he and Tessier talked about H.P. Lovecraft, No Orchids for Miss Blandish, and everything else, including the horror movies shown at the Kilburn Odeon. His writing improved. He and Susan bought a house on Hillfield Avenue in Crouch End, N8, and begat their first child, Benjamin, born during the writing of Ghost Story.

In 1979 he returned to America, living first in Westport, Connecticut, where Emma Straub was born, then in New York City, where he and his family inhabit a brownstone on the Upper West Side. He continues to enjoy the crucial friendships of Ann Lauterbach, Thom Tessier, and several others, mainly writers and jazz musicians. At some point he became conscious of the central issues of his life, which recognition made it impossible to cast them into the patterns, however imaginative, of horror literature, as least as conventionally regarded. Horror itself, on the other hand, has not abandoned him, nor can it ever, a matter for which he feels the deepest gratitude. He is a member of HWA, MWA, PEN and the Adams Round Table, and though he is without “hobbies,” remains intensely interested in jazz, as well as opera and other forms of classical music. Web Site

Works:

Novels: Marriages (1973), Under Venus (1975), Julia (1976), If you could see me now (1976), Ghost Story (1979), Shadowland (1980), Floating Dragon (1982), The Talisman (1984), Koko (1988), Mystery (1990), The Throat (1993), The Hellfire Club (1995), Mr. X (1999), Black House (2001 with Stephen King), Lost Boy Lost Girl (2003), In the Night Room (2004), A Dark Matter (2010).

Novellas & Short Stories: Blue Rose, The General's Wife (1982), Mrs God (1990), The Ghost Village (1993), Bunny is Good Bread (1993), Mr. Clubb and Mr. Cuff (1997), Pork Pie Hat (1999), The Juniper Tree and Other Stories (2010) The Ballad of Ballard and Sandrine (2011),

Wild Animals (1984), Houses without Doors (1990), Magic Terror (2000), A Little Blue Book of Rose Stories (2004), 5 Stories (2007)

My Life in PicturesIshmaelOpen AirLeeson Park and Belsize Square: Poems 1970 - 1975

Awards:

World Fantasy Award (1989 - Best Novel for Koko), Bram Stoker Award (1993 Best Novel for The Throat), World Fantasy Award (1993 - Best Novella for Ghost Village), British Fantasy Award (1994 - best Novel for The Floating Dragon), Bram Stoker Award (1998 Best Log Fiction for Mr. Clubb and Mr. Cuff ), Grand Master at World Horror Convention (1998), International Horror Guild Award (1998 - Long Form for Mr. Clubb and Mr. Cuff), Bram Stoker Award (1999 Best Novel for Mr X), Bram Stoker Award (2000 Fiction Collection for Magic Terror), International Horror Guild Award (2003 -Best Novel for Lost Boy Lost Girl), Bram Stoker Award (2003 -Best Novel for Lost Boy Lost Girl), Bram Stoker Award (2005 Lifetime Achievement), Bram Stoker Award (2007 -Collection for 5 Stories), Bram Stoker Award (2010 -Best Novel for A Dark Matter) World Fantasy Award (2010 - Lifetime Achievement)

The Book: A Dark Matter (Doubleday Publishing)On a Midwestern campus in the 1960s, a charismatic guru and his young acolytes perform a secret ritual in a local meadow. What happens is a mystery -all that remains is a gruesomely dismembered body and the shattered souls of all who were present. Forty years later, one man seeks to learn about that horrifying night, and to do so he’ll have to force those involved to examine the unspeakable events that have haunted them ever since. Unfolding through their individual stories, A Dark Matter is an electric, chilling, and unpredictable novel that proves Peter Straub to be the master of modern horror.

Read an Excerpt: Buy the Book

Presented by Edizioni XII