nei mesi scorsi vi abbiamo già parlato del bellissimo libro di Karen Maitland, La bambina delle rune (titolo originale Company of liars), in libreria per Piemme dal 21 settembre di quest'anno! Oggi abbiamo l'onore e il piacere di avere Karen ospite qui nel blog per un'intevista in cui ci parlerà meglio di se stessa e del suo romanzo, e in cui, vedrete, si svelerà essere una persona profonda e animata da vera passione per i suoi personaggi, per la loro vita, per il mondo oscuro in cui li colloca, il Medioevo europeo! Un'intervista bellissima che davvero mi ha fatto desiderare di sedermi davanti a un caffè caldo con Karen per sentirla parlare di persona per ore ed ore...

"I condannati a morte si dichiarano sempre innocenti, quando si avvicina il giorno dell’esecuzione. La gente sa che non è vero. Sono tutti colpevoli, e pagheranno. Lancio le rune dei troll, e altre tre ne lancio: frenesia, lussuria e oscenità. Chiunque mi segua, con me avrà morte e oscurità.”

Trama: Siamo nell'Inghilterra nel 1348. Un gruppo di viaggiatori dalle provenienze più disparate fugge da un'epidemia di peste. Quando i membri della compagnia cominciano a morire a uno a uno, il capo della spedizione comprende che la responsabile delle morti è una bambina che sta lanciando maledizioni contro di loro e che non vuole farli arrivare a destinazione. Tra i Top20 della classifica Bookseller, La bambina delle rune è stato selezionato dal Macavity Award tra i migliori thriller storici del 2008 e ha avuto ottime recensioni dalla critica. I diritti del libro sono stati venduti in dieci Paesi. Promosso con un'iniziativa di marketing online: disponibile sul web un sorprendente capitolo integrativo. Camelot è un venditore ambulante che viaggia da molti anni e per vivere vende reliquie false. È anche un vecchio sfigurato da una cicatrice che lo ha reso privo di un occhio. Fingendosi un reduce delle battaglie contro gli infedeli in Terra Promessa, ha fatto del marchio che porta in faccia un mezzo per sopravvivere e così vende speranza e "fede in bottiglia". Ma ora da tempo è lontano da casa e il ricordo del passato si fa vivo nella mente di Camelot, forte e nostalgico. Il venditore intraprende così la lunga strada di ritorno verso la Scozia, mentre l'imprevista esplosione della peste trasforma il suo viaggio in una fuga dall'epidemia. È il nefasto giorno di mezz'estate del 1348, quando il contagio comincia a diffondersi nel Paese e quando Camelot incontra Narigorm, una bambina albina, lettrice di rune. I suoi occhi celesti, splendenti nella cascata bianca e immacolata dei suoi capelli, lo fissano insistentemente come se volessero leggergli dentro. Un incontro fatale, il primo di una serie, che porta Camelot a proseguire il suo cammino con una nuova e bizzarra compagnia, unita dalla necessità di sopravvivere alla peste. Un mago bigotto, un cantastorie, un pittore di scene sacre, un musicista veneziano e il suo pupillo, un'esperta di erbe e infine proprio la bambina albina diventano così protagonisti di questa fuga dalla disperazione. Quando però uno del gruppo viene trovato impiccato a un albero, tra loro s'insinua il dubbio e la diffidenza. Qualcosa di più terribile della peste minaccia la loro vita, un segreto nascosto in ognuno di loro. Solo la bambina e le sue rune sanno cos'è. Per leggere la recensione completa QUI

Trama: Siamo nell'Inghilterra nel 1348. Un gruppo di viaggiatori dalle provenienze più disparate fugge da un'epidemia di peste. Quando i membri della compagnia cominciano a morire a uno a uno, il capo della spedizione comprende che la responsabile delle morti è una bambina che sta lanciando maledizioni contro di loro e che non vuole farli arrivare a destinazione. Tra i Top20 della classifica Bookseller, La bambina delle rune è stato selezionato dal Macavity Award tra i migliori thriller storici del 2008 e ha avuto ottime recensioni dalla critica. I diritti del libro sono stati venduti in dieci Paesi. Promosso con un'iniziativa di marketing online: disponibile sul web un sorprendente capitolo integrativo. Camelot è un venditore ambulante che viaggia da molti anni e per vivere vende reliquie false. È anche un vecchio sfigurato da una cicatrice che lo ha reso privo di un occhio. Fingendosi un reduce delle battaglie contro gli infedeli in Terra Promessa, ha fatto del marchio che porta in faccia un mezzo per sopravvivere e così vende speranza e "fede in bottiglia". Ma ora da tempo è lontano da casa e il ricordo del passato si fa vivo nella mente di Camelot, forte e nostalgico. Il venditore intraprende così la lunga strada di ritorno verso la Scozia, mentre l'imprevista esplosione della peste trasforma il suo viaggio in una fuga dall'epidemia. È il nefasto giorno di mezz'estate del 1348, quando il contagio comincia a diffondersi nel Paese e quando Camelot incontra Narigorm, una bambina albina, lettrice di rune. I suoi occhi celesti, splendenti nella cascata bianca e immacolata dei suoi capelli, lo fissano insistentemente come se volessero leggergli dentro. Un incontro fatale, il primo di una serie, che porta Camelot a proseguire il suo cammino con una nuova e bizzarra compagnia, unita dalla necessità di sopravvivere alla peste. Un mago bigotto, un cantastorie, un pittore di scene sacre, un musicista veneziano e il suo pupillo, un'esperta di erbe e infine proprio la bambina albina diventano così protagonisti di questa fuga dalla disperazione. Quando però uno del gruppo viene trovato impiccato a un albero, tra loro s'insinua il dubbio e la diffidenza. Qualcosa di più terribile della peste minaccia la loro vita, un segreto nascosto in ognuno di loro. Solo la bambina e le sue rune sanno cos'è. Per leggere la recensione completa QUIINTERVISTA CON KAREN MAITLAND

1. Ciao Karen. Sono lieta di darti il benvenuto sul mio blog. Ti va di presentarti ai lettori italiani che hanno letto i tuoi libri o stanno per farlo?

1. Ciao Karen. Sono lieta di darti il benvenuto sul mio blog. Ti va di presentarti ai lettori italiani che hanno letto i tuoi libri o stanno per farlo? Ciao Alessandra, grazie mille per avermi invitata sul tuo blog. Sono una scrittrice di thriller storici e sono affascinata da tutto ciò che è medievale, in particolare, dal modo in cui, in quei tempi, la superstizione, il mito e la magia permeavano la vita quotidiana degli uomini qualunque. Oltre a scrivere romanzi interamente miei, scrivo anche “murder mistery” storici a “dieci mani” con altri quattro romanzieri - Philip Gooden, Susannah Gregory, Ian Morson, e Bernard Knight, che è stato recentemente insignito di un dottorato ad honorem da parte di un’Università italiana per i suoi contributi alla Patologia Forense. Quando scriviamo insieme ci facciamo chiamare “The Medieval Murderers” ovvero “Gli assassini medievali”. Da bambina sono cresciuta fra Malta, Cipro e il Medio Oriente ma oggi vivo nello splendido borgo medievale di Lincoln, nell’est dell’Inghilterra.Prima di fare la scrittrice a tempo pieno, ho fatto molte cose fra cui lavorare in un ospedale, dance-drama e insegnare presso la facoltà di Agraria in un college in Nigeria. Per alcuni anni avevo un lavoro full time e scrivevo la sera e nei weekend ma, a partire dal 1° gennaio 2000, ho lasciato l’impiego per dedicarmi solo alla scrittura. Un fantastico inizio di millennio, per me!

2. Karen, quando hai capito che avresti voluto fare la scrittrice?Quand’ero piccola i miei non avevano la TV, quindi ero solita portarmi di nascosto una radiolina a letto e starmene sotto le coperte ad ascoltare storie e radiodrammi, molto oltre l’ora della nanna! Storie cupe di omicidi e misteri, tipo Sherlock Holmes. Fin da piccolissima mi inventavo storie d’avventura che poi raccontavo a me stessa nel letto. Infatti, da bambina, non vedevo l’ora di andare a dormire per sparire nel mio mondo di storie. Il momento in cui ho deciso di fare la scrittrice è stato però all’età di quattordici anni, quando ho letto il mio primo libro da grandi, Il potere e la gloria di Graham Greene. Fino ad allora i libri per ragazzi mi erano sempre sembrati un po’ stupidi e vuoti. Eroi ed eroine erano sempre incredibilmente coraggiosi, belli e scaltri e sapevo che, all’ultimo momento, se la cavavano sempre. Sono cresciuta in Paesi segnati dalla guerra. Ho visto persone uccise e sapevo che nella vita reale la cavalleria non arrivava giù dalla collina a salvarli. Ma leggendo Il potere e la gloria ho capito che i libri potevano parlare anche di persone reali, come me – codardi, gente non bella, con debolezze umane. Ho anche scoperto che nei romanzi, come nella vita, non sempre l’eroe si salva nell’ultima pagina. Ed è lì che ho capito di amare i libri.

3. Cosa fai mentre scrivi? Hai un tuo processo creativo particolare?

Quando butto giù la prima bozza, tendo a usare una tecnica che io chiamo scrittura a “osso nudo”. Creo l’immagine della scena nella mia mente, magari un litigio o una scena d’azione. Poi la descrivo come se si stesse svolgendo davanti ai miei occhi, spesso pronunciando i dialoghi a voce alta, ma non metto punteggiatura, non faccio descrizioni, non scrivo nemmeno chi dice cosa. Solo butto giù la scena più alla svelta che posso, quasi in tempo reale, come la stessi osservando. Il giorno dopo ci torno sopra e la sviluppo. Quando devo inventarmi un intreccio, vado in un remoto cottage che affitto per circa una settimana a Norfolk, nelle paludi salmastre. Se rimango impantanata in un problema di trama, esco dal cottage e cammino attraverso la palude fino alla spiaggia, dove le onde si infrangono sulla sponda. Di solito fa molto freddo e non c’è nessun altro in quel luogo selvaggio, ma nel tempo che torno dalla passeggiata, il mio cervello ha risolto il problema.

4. Quando non scrivi, che tipo di libri ti piace leggere?

Non leggo romanzi medievali mentre li scrivo, per non essere influenzata da libri o descrizioni altrui. Mi piacciono i thriller moderni, la letteratura di viaggio, vecchia e nuova, il realismo magico e i gialli a fumetti. Leggo anche libri di leggende di vari Paesi. Credo che i racconti e i miti locali dicano tantissimo sul carattere del popolo e sul paesaggio di quella determinata regione. Sono fissata con gli audiolibri versione integrale, che ascolto sul lettore CD, mentre faccio le faccende di casa, mentre cucino o stiro. Mi sembra che così posso conoscere molti più libri, e che ascoltare qualcuno leggere il libro mi aiuta a sentire il ritmo dello stile e del linguaggio dell’autore con maggior facilità che non quando leggo io stessa. Mi spinge anche ad affrontare autori e generi che normalmente non leggerei, perché esaurisco in fretta i miei preferiti.

5. Cosa ti ha ispirato a scrivere La bambina delle rune? L’ispirazione per questo libro è venuta in seguito a un viaggio attraverso la Gran Bretagna. Mi era stato commissionato un tour di tre mesi con un’organizzazione chiamata “National Rural Touring Forum”, che porta piccole compagnie teatrali in remote comunità rurali che vivono troppo lontano dalle città principali per avere la possibilità di vedere gli spettacoli dal vivo. Mi era stato chiesto di unirmi a un gruppo di danza indiano e a uno di narratori inglesi, per scrivere un libro circa le cose che succedevano e i posti dove si esibivano. Abbiamo viaggiato nel freddo pungente dell’inverno, lungo strade di campagna non illuminate, esibendoci in minuscole sale comuni non riscaldate: molti dei villaggi visitati erano antichi, fondati prima del 1066. E ho cominciato a pensare a quelle persone che, nel medioevo, si guadagnavano da vivere per strada, quelli che non avevano una casa ma vagabondavano di villaggio in villaggio, come venditori ambulanti, musicisti, guaritori e giocolieri. Mentre percorrevamo le vie fredde e buie, ho cominciato a immaginare come fosse la vita dei viaggiatori a quei tempi, spostandosi a piedi di luogo in luogo, senza sapere cosa avrebbero trovato al loro arrivo, se li avrebbero accolti o scacciati, se avrebbero trovato cibo o riparo. Da qui è nata la scintilla per Company of Liars/La bambina delle rune.

5. Cosa ti ha ispirato a scrivere La bambina delle rune? L’ispirazione per questo libro è venuta in seguito a un viaggio attraverso la Gran Bretagna. Mi era stato commissionato un tour di tre mesi con un’organizzazione chiamata “National Rural Touring Forum”, che porta piccole compagnie teatrali in remote comunità rurali che vivono troppo lontano dalle città principali per avere la possibilità di vedere gli spettacoli dal vivo. Mi era stato chiesto di unirmi a un gruppo di danza indiano e a uno di narratori inglesi, per scrivere un libro circa le cose che succedevano e i posti dove si esibivano. Abbiamo viaggiato nel freddo pungente dell’inverno, lungo strade di campagna non illuminate, esibendoci in minuscole sale comuni non riscaldate: molti dei villaggi visitati erano antichi, fondati prima del 1066. E ho cominciato a pensare a quelle persone che, nel medioevo, si guadagnavano da vivere per strada, quelli che non avevano una casa ma vagabondavano di villaggio in villaggio, come venditori ambulanti, musicisti, guaritori e giocolieri. Mentre percorrevamo le vie fredde e buie, ho cominciato a immaginare come fosse la vita dei viaggiatori a quei tempi, spostandosi a piedi di luogo in luogo, senza sapere cosa avrebbero trovato al loro arrivo, se li avrebbero accolti o scacciati, se avrebbero trovato cibo o riparo. Da qui è nata la scintilla per Company of Liars/La bambina delle rune. 6. Che tipo di ricerche svolgi per i tuoi libri? Molti dei luoghi citati li ho visitati durante il tour o in altre occasioni. Alcuni capitoli importanti del libro, tuttavia, sono ambientati in una cappella per le messe in suffragio situata su un ponte, in cui il gruppo si nasconde per sfuggire alla peste. Di queste cappelle non ne sono rimaste molte in Gran Bretagna perché, essendo costruite in mezzo ai fiumi, sono state per lo più spazzate via da tempeste e inondazioni. Ne ho però trovata una a Wakefield che è rimasta virtualmente immutata dal medioevo e ci sono rimasta per un po’, sdraiandomi sul pavimento e ascoltando ciò che i miei personaggi avrebbero udito dormendoci dentro. Oltre a fare ricerche sulla storia, sui vestiti, sulle feste e le fiere dell’epoca, ho anche coltivato le erbe di cui parlo e cucinato alcuni dei cibi per poterli descrivere. Ho letto tutto quel che potevo circa quelle che, nel medioevo, si credeva fossero le cause della peste e cosa facevano per cercare di proteggersi, compreso inscenare “il matrimonio degli storpi”, come accade in una scena significativa del romanzo. Si tratta di una tradizione che scoprii in un museo di Cracovia, ma ho poi scoperto che il “matrimonio degli storpi” era una pratica comune in molti paesi e villaggi britannici e in altre parti del mondo come un modo per evitare malattie e disastri. Un altro elemento importante della storia sono le rune. Le conoscevo come forma di scrittura, essendo stata in Irlanda e Islanda. E con mia grande soddisfazione, anni fa durante una vacanza, ho trovato anche alcune rune antiche inscritte nel muro di un castello del nord Italia. Tuttavia sapevo poco del loro uso per la divinazione quindi ho fatto diverse ricerche sulla lettura delle rune, ho persino chiesto a un maestro di lettura delle rune che pratica ancora oggi di mostrarmi come vengano lanciate e interpretate. È stato lui a insegnarmi che anche gli spazi fra le rune possono essere letti, cosa che non avevo trovato in nessun libro.

7. Ci sono, nel libro, degli stupendi passaggi in cui descrivi la bellezza unica di Venezia: la scelta di dare a questa città un ruolo importante nel passato di Rodrigo e Jofre è motivata solo dalla sua importanza storica o da una tua predilezione personale per Venezia? Sono felice se ti sembra che io abbia catturato un po’ della magia di Venezia. Ci sono stata diverse volte, la prima ero un’adolescente. Mi innamorai a prima vista delle sue meraviglie e dell’atmosfera. Molte città hanno una lunga storia, ma quella di Venezia sembra galleggiare nell’aria, trasudare dalle pietre, più che in ogni altro posto. Venezia era uno snodo fondamentale dei commerci per tutto il mondo, eppure era fiera della sua indipendenza. Altri centri di commercio sembrano perdere la propria identità a causa delle molteplici influenze culturali, ma non Venezia. Anzi, al contrario: ovunque andassero, i veneziani lasciavano il segno. Non posso fare a meno di scrivere di questa città, perché mi basta metterci piede per immaginare storie e segreti che si celano sotto le acque e dietro la porta di ogni monumento.

8. Il capitolo extra ha un passaggio piuttosto forte… non che la cruda realtà manchi nel romanzo, che invero è molto realistico, ma quando si parla di bambini è più difficile, dal punto di vista emozionale, affrontarla. È per questo che non è stato incluso nel libro ed è rimasto un extra, sebbene sia fondamentale per capire del tutto la storia? In realtà il capitolo extra è stato scritto dopo l’uscita del libro in Inghilterra. In origine, era mia intenzione lasciare che il segreto di Rodrigo rimanesse tale, lasciando ai lettori la possibilità di immaginare di cosa potesse trattarsi, e cosa succede fra i protagonisti rimasti e la piccola Narigorm. Quando le librerie Waterstones mi chiesero un capitolo extra da inserire nell’edizione limitata in paperback, pensai di raccontare la storia “non detta” di Rodrigo, che avevo in testa, lasciando che le conseguenze per Rodrigo facessero il proprio corso. Rodrigo è il personaggio di cui sono, si potrebbe dire, segretamente innamorata, ecco perché mi è costato tanto farlo soffrire. Alcuni lettori inglesi hanno affermato di preferire il libro senza il capitolo extra perché per loro è meglio immaginare quello che succede – mentre altri lo hanno apprezzato. Ancora non so cosa ne penseranno i lettori italiani. E sì, sono d’accordo che, dal punto di vista emozionale, la violenza sui bambini è una delle cose più difficili da affrontare, ma purtroppo a quei tempi i bambini erano trattati alla stregua di merci. Per esempio, nel 1100 un nobile di nome John, un ufficiale del re, mandò il figlio di cinque anni in ostaggio a re Stefano come prova che non avrebbe tradito il sovrano. In realtà John usò il figlio solo per guadagnare tempo, e quando sollevò un esercito contro il re, questi minacciò di impiccargli il figlioletto. John replicò: “Procedete pure. Non mi importa, posso farne altri, di figli”. Per fortuna il re si intenerì e non impiccò il bambino ma molti altri, in quell’epoca, avrebbero ucciso un ragazzino senza neanche pensarci.

8. Il capitolo extra ha un passaggio piuttosto forte… non che la cruda realtà manchi nel romanzo, che invero è molto realistico, ma quando si parla di bambini è più difficile, dal punto di vista emozionale, affrontarla. È per questo che non è stato incluso nel libro ed è rimasto un extra, sebbene sia fondamentale per capire del tutto la storia? In realtà il capitolo extra è stato scritto dopo l’uscita del libro in Inghilterra. In origine, era mia intenzione lasciare che il segreto di Rodrigo rimanesse tale, lasciando ai lettori la possibilità di immaginare di cosa potesse trattarsi, e cosa succede fra i protagonisti rimasti e la piccola Narigorm. Quando le librerie Waterstones mi chiesero un capitolo extra da inserire nell’edizione limitata in paperback, pensai di raccontare la storia “non detta” di Rodrigo, che avevo in testa, lasciando che le conseguenze per Rodrigo facessero il proprio corso. Rodrigo è il personaggio di cui sono, si potrebbe dire, segretamente innamorata, ecco perché mi è costato tanto farlo soffrire. Alcuni lettori inglesi hanno affermato di preferire il libro senza il capitolo extra perché per loro è meglio immaginare quello che succede – mentre altri lo hanno apprezzato. Ancora non so cosa ne penseranno i lettori italiani. E sì, sono d’accordo che, dal punto di vista emozionale, la violenza sui bambini è una delle cose più difficili da affrontare, ma purtroppo a quei tempi i bambini erano trattati alla stregua di merci. Per esempio, nel 1100 un nobile di nome John, un ufficiale del re, mandò il figlio di cinque anni in ostaggio a re Stefano come prova che non avrebbe tradito il sovrano. In realtà John usò il figlio solo per guadagnare tempo, e quando sollevò un esercito contro il re, questi minacciò di impiccargli il figlioletto. John replicò: “Procedete pure. Non mi importa, posso farne altri, di figli”. Per fortuna il re si intenerì e non impiccò il bambino ma molti altri, in quell’epoca, avrebbero ucciso un ragazzino senza neanche pensarci. 9. Sei riuscita a dipingere molto bene la fuga disperata dalla peste che si diffondeva a velocità allarmante e sei stata sempre capace, nel complesso, di coinvolgere il lettore\lettrice, che pure è consapevole che la peste finirà: leggendo, ci si trova circondati e intrappolati dal morbo e quasi si dimentica che non finirà per ingoiare tutta l’umanità… cosa hai richiamato nella tua mente per veicolare tanto bene questo senso di claustrofobica ineluttabilità? Sono contentissima che tu abbia percepito tutto questo. Credo che una delle cose che condividiamo con le generazioni passate, sia il sentimento di terrore e impotenza quando ci troviamo coinvolti in situazioni di cui non abbiamo il controllo – inondazioni, tempeste, terremoti. Abbiamo la stessa sensazione di inanità di fronte al collasso finanziario delle grandi istituzioni, quando vediamo i nostri soldi scomparire ma, come individui, non possiamo fare nulla per impedirlo. Nelle ultime decadi abbiamo visto il panico causato dalle nuove epidemie come l’AIDS, l’influenza dei polli o la suina e quanta paura ha la gente di rimanere infettata. Reagisce come nel medioevo: facendo scorte di cibo, evitando gli stranieri e isolandosi. La natura umana cambia poco. Ho lavorato in Nigeria, durante la Guerra Civile e a Belfast, Irlanda del Nord, nei momenti caldi del terrorismo. Spesso da semplice passante mi sono ritrovata coinvolta in scontri violenti, in due occasioni ero dentro un edificio in cui è esplosa una bomba. Per fortuna non sono mai rimasta ferita, a differenza di alcuni miei amici, ma ricordo bene il senso di impotenza e panico, miei e delle persone vicine, quando non c’è niente che tu possa fare per fermare il corso degli eventi. Per scrivere ho attinto a esperienze ed emozioni di questo tipo.

10. La scelta di personaggi che non sono certo persone comuni ma che appartengono alle classi più povere, dando così al lettore la possibilità di vedere attraverso gli occhi della gente e non dei grandi della storia, in altre parole di vedere la storia “dal basso”, è stata motivata dal desiderio di far immedesimare profondamente il lettore e di far meglio comprendere la Storia? Prima di scrivere romanzi storici, spesso mi commissionavano libri di non-fiction, per scrivere i quali dovevo recarmi nei centri storici, nelle miniere, nelle comunità di pescatori o nelle fabbriche e intervistare la gente. Ho imparato presto che sono le persone più ordinarie ad avere le vite più straordinarie. Molte di queste persone portavano con sé abilità, storie ed esperienze che sarebbero morte con loro. Re e governanti sono importanti nella storia, ma sono le persone qualunque, quelle che vivono e muoiono senza lasciare traccia, a costruire davvero un Paese e una cultura – i fattori, le casalinghe, i soldati, i tessitori, i pescatori, i tagliapietre, i fabbri – senza di loro la Storia non esisterebbe. Voglio raccontare le loro vicende, scrivere di vite e persone che la Storia non ricorda. Queste storie sono le più affascinanti. Voglio, nel mio piccolo, dare a queste persone che vengono dal basso il posto che spetta loro nella Storia. Inoltre, come hai detto, voglio che i miei lettori si identifichino coi miei personaggi medievali, che abbiano l’impressione di poter entrare in un bar o in un caffé e vederli lì seduti, di potersi bere una cosa insieme e scoprire che le loro speranze i sogni, le paure, le emozioni,non sono poi così diversi da quelli che abbiamo noi oggi.

11. Le due fiabe che Cygnus racconta, oltre a evocare immagini molto poetiche sul personaggio, contengono realtà importanti per l’economia del romanzo… ma se “I sei cigni” è una fiaba ben nota dei fratelli Grimm, devo ammettere che la seconda non l’ho mai sentita… l’hai scritta tu? In epoca precristiana giravano per tutta l’Europa storie di esseri soprannaturali che vivevano in forma di cigno, creature magiche dell’aria e dell’acqua, ma che potevano, a loro discrezione, trasformarsi in umani e, con tale aspetto, fare l’amore con l’uomo o la donna che desideravano, poi, quando si stancavano, si ritrasformavano in cigno e se ne volavano via. Per la chiesa cristiana queste storie erano blasfeme perché gli uccelli e gli altri animali erano considerati esseri inferiori rispetto all’uomo… quindi come poteva qualcuno scegliere di essere un cigno? Tuttavia la Chiesa non poteva cancellare queste storie, quindi le modificò. Nelle loro versioni qualcuno veniva trasformato da una strega o da un mago cattivo in un vile uccello e poteva riguadagnare la propria forma umana solo attraverso le virtù cavalleresche dell’amore e della fedeltà. La favola de “I sei cigni” è un tipico esempio di fiaba “cristianizzata”. Per quanto riguarda la seconda fiaba narrata da Cygnus, la prima parte è una tipica storia pre-cristiana, anche se, ovviamente, vi ho aggiunto dei dettagli. Cygnus racconta della ragazza-cigno che si trasforma in essere umano perché nel romanzo tutti credono che lui dovrebbe aspirare a essere del tutto umano, mentre, in effetti, lui vorrebbe diventare davvero un cigno, con tutta la libertà che ciò comporta. La seconda parte della storia si basa su una bugia medievale ufficiale. Godfrey Cavaliere Comandante di Gerusalemme divenne, dopo le crociate, uno dei cavalieri più famosi e ricchi d’Europa. Eppure cominciarono a circolare voci che lui non fosse di nobili origini, dato che nessuno riusciva a rintracciarne il lignaggio. L’intero sistema medievale si basava sull’idea che solo chi era di nobili origini potesse possedere le virtù cavalleresche e che nessuno potesse elevarsi al di sopra della classe sociale cui apparteneva per nascita. Infatti, se l’uomo qualunque avesse avuto il concetto che chiunque di bassa estrazione potesse aspirare a diventare un governante potente, poi il popolo avrebbe potuto insorgere e tentare di rovesciare i propri signori. Fu dunque commissionata una ballata a un menestrello reale francese affinché inventasse un nobile lignaggio per Godfrey. L’artista ebbe la brillante idea di tirar fuori che il nonno di Godfrey fosse un cavaliere misterioso – il cavaliere del Cigno – il che spiegava perché nessuno fosse in grado di rintracciare gli antenati di Godfrey, rendendolo al contempo discendente di un re, quindi di sangue reale e quindi adatto a regnare. Oggi si stenta a credere una cosa del genere, ma questa bugia ufficiale ebbe un tale successo che diverse altre ricche famiglie europee adottarono lo stesso stratagemma per giustificare la propria mancanza di un lignaggio. Ho basato la seconda parte della storia narrata da Cygnus su questa antica ballata medievale, sebbene con qualche aggiunta: volevo usare questa storia per riflettere sul fatto che non sono solo i singoli individui a inventarsi il proprio passato e a dire bugie, ma anche delle potenti organizzazioni.

12. C’è qualche nuovo autore che ha suscitato il tuo interesse? Ho appena finito di leggere un eccellente romanzo storico di debutto The Lady’s Slipper di Deborah Swift. È ambientato nel 1660 e parla di una rara orchidea che divide una comunità perché varie persone cercano di impossessarsene per i propri fini. Sono a metà di un thriller moderno molto avvincente, The Woman Before Me, un’altra opera prima. È un thriller psicologico moderno, circa una donna accusata di un incendio doloso in cui è morto un bambino. La donna cerca di convincere l’ufficiale giudiziario a lasciarla uscire di prigione, ma non è che si tratta di un inganno? Non è un libro nuovo, ma uno dei miei romanzi preferiti fra quelli da brividi è Spider Light di Sarah Rayne. È ambientato sia ai giorni d’oggi che in epoca vittoriana: una donna del nostro tempo si rifugia per ragioni di sicurezza in un remoto cottage e scopre, nei dintorni del suo nascondiglio, i resti di un antico ospedale psichiatrico con un lato oscuro e terrificante. I due mondi entrano gradualmente in contatto. Ho fatto l’errore di leggere questo libro da sola, in una notte buia e tempestosa, nel remoto cottage nella palude, dove ero andata per scrivere e dove non ci sono telefoni, e-mail e neppure la copertura del cellulare. Spider Light è un romanzo tanto oscuro e d’atmosfera che mi sono ritrovata a trasalire ad ogni scricchiolio e fruscio della notte!

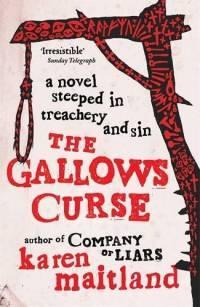

12. C’è qualche nuovo autore che ha suscitato il tuo interesse? Ho appena finito di leggere un eccellente romanzo storico di debutto The Lady’s Slipper di Deborah Swift. È ambientato nel 1660 e parla di una rara orchidea che divide una comunità perché varie persone cercano di impossessarsene per i propri fini. Sono a metà di un thriller moderno molto avvincente, The Woman Before Me, un’altra opera prima. È un thriller psicologico moderno, circa una donna accusata di un incendio doloso in cui è morto un bambino. La donna cerca di convincere l’ufficiale giudiziario a lasciarla uscire di prigione, ma non è che si tratta di un inganno? Non è un libro nuovo, ma uno dei miei romanzi preferiti fra quelli da brividi è Spider Light di Sarah Rayne. È ambientato sia ai giorni d’oggi che in epoca vittoriana: una donna del nostro tempo si rifugia per ragioni di sicurezza in un remoto cottage e scopre, nei dintorni del suo nascondiglio, i resti di un antico ospedale psichiatrico con un lato oscuro e terrificante. I due mondi entrano gradualmente in contatto. Ho fatto l’errore di leggere questo libro da sola, in una notte buia e tempestosa, nel remoto cottage nella palude, dove ero andata per scrivere e dove non ci sono telefoni, e-mail e neppure la copertura del cellulare. Spider Light è un romanzo tanto oscuro e d’atmosfera che mi sono ritrovata a trasalire ad ogni scricchiolio e fruscio della notte!  13. Al momento stai lavorando a qualche nuovo progetto? Al mio nuovo thriller medievale The Gallows Curse, che dovrebbe uscire nel Regno Unito a primavera. È ambientato in Inghilterra, nel 1210, quando l’intero paese era scomunicato per un periodo di sei anni. Uno dei due protagonisti è un eunuco italiano, Raffaele, che ha combattuto le crociate ed è arrivato in Inghilterra come attendente di un cavaliere inglese. Il cavaliere sta morendo ma non si trova un prete per assolverlo e l’uomo si è macchiato di un peccato terribile che non ha mai confessato a nessuno. Raffaele giura avventatamente di cancellare in qualche modo questo peccato dall’anima del caro amico, un giuramento disperato a mezzo del quale un innocente si trova coinvolto in disastri e omicidi. Al momento sto anche correndo per finire un altro romanzo The Falcons of Fire and Ice che si svolge nel 1564 fra Portogallo e Islanda. È stato un anno orribile in cui marrani, musulmani e luterani venivano torturati e messi al rogo dall’inquisizione portoghese, mentre in Islanda i cattolici erano perseguitati e uccisi a causa della Riforma. Sto anche cercando di pensare la trama per il mio racconto nella prossima raccolta coi “Medieval Murderers”.

13. Al momento stai lavorando a qualche nuovo progetto? Al mio nuovo thriller medievale The Gallows Curse, che dovrebbe uscire nel Regno Unito a primavera. È ambientato in Inghilterra, nel 1210, quando l’intero paese era scomunicato per un periodo di sei anni. Uno dei due protagonisti è un eunuco italiano, Raffaele, che ha combattuto le crociate ed è arrivato in Inghilterra come attendente di un cavaliere inglese. Il cavaliere sta morendo ma non si trova un prete per assolverlo e l’uomo si è macchiato di un peccato terribile che non ha mai confessato a nessuno. Raffaele giura avventatamente di cancellare in qualche modo questo peccato dall’anima del caro amico, un giuramento disperato a mezzo del quale un innocente si trova coinvolto in disastri e omicidi. Al momento sto anche correndo per finire un altro romanzo The Falcons of Fire and Ice che si svolge nel 1564 fra Portogallo e Islanda. È stato un anno orribile in cui marrani, musulmani e luterani venivano torturati e messi al rogo dall’inquisizione portoghese, mentre in Islanda i cattolici erano perseguitati e uccisi a causa della Riforma. Sto anche cercando di pensare la trama per il mio racconto nella prossima raccolta coi “Medieval Murderers”. 14. Grazie mille. È stato veramente un grande piacere per me intervistarti. C’è ancora qualcosa che vuoi dirci prima di salutare?

Vorrei dirvi quanto mi emoziona l’idea che il mio romanzo sia stato tradotto in italiano. Ogni volta che vengo in vacanza in Italia, mi sento sempre come se tornassi a casa, forse perché ho trascorso l’infanzia a Malta e ci sono molte somiglianze, nell’architettura e nella cultura. Non vedo l’ora di tornare nel vostro Paese, mi sono sempre trovata molto bene, indipendentemente da quale parte dello stivale abbia visitato! Grazie di aver letto questa intervista sul blog e di avermi dato al possibilità di condividere alcuni dei miei pensieri con voi. E grazie anche per aver letto Company of Liars/La bambina delle rune. Spero tanto che vi sia piaciuto.

INTERVIEW WITH KAREN MAITLAND

1. Hi Karen. I'm very happy to welcome on my blog. Would you like to introduce yourself to the Italian readers who have read your novels or who are going to do?

Hi, Alessandra and thank you so much for inviting me on to your blog. I am a historical thriller writer and I am fascinated by all things medieval and in especially the way in which superstition, myth and magic was woven through the everyday lives of ordinary people in the Middle Ages. As well as writing my own full length novels, I also write joint historical murder-mystery books with four other novelists – Philip Gooden, Susannah Gregory, Ian Morson, and Bernard Knight who recently was awarded an honorary doctorate from a University in Italy for his services to Forensic Pathology. When we write together we call ourselves The Medieval Murderers. As a child I grew up in Malta, Cypress and the Middle East, but I now live in the beautiful medieval city of Lincoln in the east of England. Before I become a full-time writer, I did a variety of jobs including working in a hospital, dance-drama and teaching in a College of Agriculture in Nigeria. For a few years I worked full-time and wrote in the evenings and weekends, but on the 1st January 2000, I gave up the day-job to become a full-time writer. A great start to the new millennium for me.

2. Karen, when was the first moment you knew you wanted to become a writer? My parents didn’t have TV when I was a child, so I would smuggle a tiny radio into bed and listen under the blankets to plays and stories on the radio long after I should have been asleep – dark tales of murder and mystery such as Sherlock Holmes. Ever since I was tiny I used to make up adventure stories which I’d tell myself in bed. In fact, as a child, I couldn’t wait to go to bed to disappear into my own world of stories. The moment I knew I wanted to become a writer was when I was 14 years old and I read my first adult book The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene. Up to then I’d thought children’s books rather silly and pointless. The heroes and heroines were always impossibly brave, handsome and clever, and I knew the hero would always be saved at the last moment. I’d grown up in war-torn countries. As a child I’d seen people killed and I knew that in real life the cavalry did not come charging over the hill to rescue them. But when I read The Power and the Glory, I realised that for the first time that books could be about real people like me – cowards, people who weren’t beautiful, people with human weaknesses. I also discovered that novels, like life, didn’t always have to have the hero saved on the final page. That’s when I first learned to love books.

3. What do you do while are you writing? Have you a particular creative process? When I am writing a first draft, I tend to use technique that I call ‘bare-bones’ writing. I picture the scene in my head, perhaps an argument or an action scene. Then I write as if it is being played out in front of my eyes, often speaking the dialogue aloud, but I don’t put in any punctuation, or description not even who said what. I just get the scene down as fast as possible, almost in real time as if I am watching it. The next day I go back and flesh it out. When I am trying to think up a plot I go down to a remote cottage I hire for a week or so in Norfolk, on the salt marshes. If I get struck on a plot problem I walk straight out of the door across the marshes to the beach where the waves are thundering onto the shore. Usually it so cold and wild on the beach, there is no one else there, but the time I get back from my walk, my brain has sorted out the plot problem.

4. When you are not writing what kind of books do you like to read? I don’t read medieval novels when I’m writing them, in case I am influenced by other people’s books or descriptions. But I love modern thrillers, new and old travel writing, magic realism and I love comic detective books. I also read books of legends about different countries. I think local folk tales and myths tell you so much about the character of the people and landscape of that region. I am addicted to listening to unabridged talking books on the CD player, so whenever I am doing some domestic chore like cooking or ironing, I listen to a talking book. I find I can get through many more books that way, and listening to a book being read helps me to hear the rhythm of the author’s style and language much more easily than if I read it. It also makes me tackle new authors and genres I wouldn’t normally read, because I quickly run out of my favourites.

5. What inspired you to write La bambina delle rune? The inspiration for this novel came from a tour through Britain. I was commissioned to tour for three months with an organisation called the National Rural Touring Forum, which brings small theatre companies to small isolated rural communities who live too far from main towns to be able to see live performances. I was asked to tour with an Indian dance and English story telling group to write a book about what happened and the places they performed in. We travelled in a bitterly cold winter, on unlit country roads, playing in tiny unheated village halls. Many of the places we went to were ancient villages founded before 1066. And I started thinking about the people in the Middle Ages who earned their living on the road, those who had no home, but tramped from village to village as peddlers, musicians, healers and jugglers. As we travelled along the cold dark roads, I began to imagine what it must have been like for travellers back in those days who walked from place to place never knowing what they would find when they arrived or if they would be welcome or driven out or if they would find food or lodgings. It was this experience that sparked the idea for Company of Liars.

6. What type of research did you do for your book? Many of the places mentioned in the book I had either visited on the tour or at other times. But some important chapters in the book are set in a chantry bridge chapel where the group hide from the plague. There aren’t many of these chapels left in Britain because, being built in the centre of rivers, storms and floods have swept them away. However I found one in Wakefield which is virtually unchanged since the Middle Ages and spent time in that, lying on the floor, listening to what my characters might have heard if you had they had slept in it. In addition to research into the history, dress, markets and fairs of this period, I also grew the herbs I mention in the novel and cooked some of food so that I could describe it. I read as much as possible about what people in the Middle Ages thought were the causes of the plague and what they did to try to protect themselves, including staging the ‘Cripples’ or ‘Beggars Wedding, which is a significant scene in the novel. This was a custom I first came across in a museum in Krakow, but I later discovered the ‘beggars wedding’ was a custom practised by many towns and villages in Britain and other parts of Europe as a way of warding off sickness or disaster. Another important element of the novel is the runes. I was familiar with them as a form of writing, having spent time in Ireland and Iceland. And to my delight, on a holiday a few years ago I also found some ancient runes inscribed on the wall in a castle in Northern Italy. But I knew little about how runes were used in fortunetelling, so did a great deal of research about rune-reading including asking a master rune reader who practises today to show me how runes are cast and read. He was the man who taught me what I have never found in a book, that the spaces between some runes can be read too.

7. There are some amazing passages in the book in which you describe the unique beauty of Venice; the choice to give to this city an important role in Rodrigo and Jofre's past was just motivated by its historical role or by your own predilection for Venice? I am glad you felt I captured a little of the magic of Venice. I have visited Venice several times, the first time in my teens. I fell in love with its wonder and atmosphere from the moment I first saw it. Many cities have a long history, but the history of Venice seems to hang in its air and seep up from its stones, more than in any other city. Venice was such an important trading centre for the whole world and yet it has this fierce independence. Other trading cities seemed loose their identity because of all the cultural influences, but Venice hasn’t. Quite the reverse the Venetians left their mark where ever they went. It’s a city I just can’t help writing about, because I only have to set foot in it to imagine the stories and secrets that lie beneath its waters and behind the door of every building

8. The extra chapter has a quite tough passage... Not that cruel reality is missing during the novel, for it is very realistic, but when it's about children it's harder, emotionally, to deal with it! Is it why it wasn't included in the paper book and remained an extra, even though it's fundamental to fully understand the story? The extra chapter wasn’t in fact written until after the hardback book had come out in England. Originally it had been my intention to leave Rodrigo’s secret untold and to have readers to imagine what his secret might have been, and what happens between the remaining characters and the child Narigorm. When the booksellers Waterstones asked for an additional chapter to put in limited edition paperback. I thought I would tell the untold story which was in my head and let the consequences be played out for Rodrigo. Rodrigo is the character I am almost secretly in love with, which is why I had such a hard time making him suffer. Some British readers say they like the novel without the extra chapter – they prefer to imagine what happen – others like to have this new chapter. I don’t know yet which Italian readers will prefer. Yes, I agree, cruelty to children is the hardest thing emotionally to deal with, but sadly children in those days were treated almost as commodities. For example, in the 1100’s a nobleman called, John, who was the King’s marshal sent his own five year old son to King Stephen as a hostage to prove he would not betray the King. But John was merely using that promise to buy time and when he did raise an army against the king, the king threatened to hang his five year old son. John replied ‘Go ahead hang him. I don’t care. I can easily breed more sons.’ Fortunately, the King relented and didn’t hang the child, but many others at that time thought nothing of slaying children.

9. You managed to depict very well the desperate escape from the plague that diffunded at allarming speed, and overall you managed to involve the reader even if s/he know that the plague will end, s/he finds him/herself surrounded and trapped by the illness and almost forgot that it won't swallow the entire humanity... What did you recalled in your mind to manage to convey so well this sens of claustrophobic unavoidability? I am delighted that you thought that sense came across. I think one of the things we share with past generations is that feeling of terror and helpless when we are caught up in situations over which we have no control – floods, storms, earthquakes. We have those same feelings of powerlessness when we are caught up in the financial collapse of big institutions, when we watch our money disappear and as individuals we can do nothing to stop it. In the last few decades we’ve seen the panic that ensues if a new epidemic such as Aids, bird-flu or swine-flu breaks out and people are frightened of catching it. They react much as they did in the Middle Ages, trying to stock-pile food, shun strangers and shut themselves away. Human nature doesn’t change much. I worked in Nigeria during a civil war and in Belfast, Northern Ireland and the height of the terrorist conflict there. I often found myself caught up as a bystander in violent riots and on two separate occasions I was inside buildings in which bombs went off. Fortunately I escaped injury, unlike some of friends, but I vividly recall that sense of powerlessness and panic in me and in those around me, when there nothing you can do stop events unfolding. I draw on those kinds of emotions and experiences when I write.

10. Choosing characters who are surely uncommon people, but who belong to the poorest classes, which let the reader see through people's eyes and not the greatest of history's, in other words to see history from the bottom, was something motivated by the desire of a strong immedesimation of the reader and a better comprehension of history? Before I started writing historical fiction, I was commissioned to write a number of non-fiction books which involved going into inner-city communities, into mines, or fishing communities and industries to interview people. I quickly learned that the most ordinary people have the most extraordinary lives. Many of these people had skills, stories and experiences that would die with them when they died. Kings and rulers are important in history, but it is the ordinary people, those who live and die without trace, who really build a country and a culture – the farmers, housewives, soldiers, weavers, fishermen, stone-workers, metal-workers – without them there would be no history. I want to tell their story, to write about the lives of the people who are not recorded. These are the most fascinating stories of all. I want, in some small way, for these people at the bottom to be given their rightful place in history. And as you say, I want my readers to identify with my characters from the Middle Ages, to feel they could go into a café or a bar and see them sitting there, maybe have a drink with them and realise that their hopes, dreams, fears, and emotions are not so very different from ours today.

11. The two fairytales which Cygnus tell, besides calling up very poetic images referred to the character, show important truths for te ecpnpmy of the story; but if "The Six Swans" by Grimm brothers it's pretty well known, I have to admit I've never heard about the second one... Did you write it? All over Europe in pre-Christain days there were tales of supernatural beings who lived their lives as swans, magical creatures of air and water, but who could choose to transform themselves into humans and in that guise make love to a man or woman they desired, then when they were bored, they would become swans again and fly off. To the Christian church such tales were blasphemy, because they considered birds and beasts lower than humans, so why would any human choose to be a swan? But the Church couldn’t suppress these stories, so they changed them. Now, in their version, it was a human who was wickedly enchanted by a witch or sorcerer into becoming a lowly bird, and they could only regain their human form through the knightly virtues of love and faithfulness. A typical example of one of those Christianised tales is the Six Swans. In the second tale Cygnus tells, the first part of the story is typical of one of those original pre-Christian tales, though obviously I have added my own detail to it. Cygnus tells this story of the swan maiden who transform herself into a human, because in the novel everyone thinks he should want to be fully human, but in fact he wants to be fully swan with all the freedom that brings. The second part of the tale is based on an official medieval lie. Godfrey, Knight Commander of Jerusalem, become one of the most famous and wealthy knights in Europe after the Crusades. But rumours began to circulate that he was not of noble birth, because no one could trace his linage. The whole of the feudal system was based on the idea that only those of noble birth had the knightly virtues and that people could not rise above the status into which they had been born. If the ordinary man got hold of the idea that anyone of lowly birth could rise to be a powerful ruler, then they might have risen up and tried to overthrow their masters. So, a royal French minstrel was commissioned to write a ballad inventing a noble linage for Godfrey. This minstrel came up with the brilliant idea that if Godfrey’s grandfather was a mysterious knight – the Swan knight – then that would explain why no one could trace Godfrey’s lineage, while at the same time making him a descendant of a king meant that he had ‘royal blood’ and was therefore fit to rule. It may be hard to believe now, but this official state lie was so successful that several other wealthy families in Europe adopted it to explain their lack of linage. I based the second part of the story Cygnus tells on this old medieval ballad, though with some additions. I wanted to use this story to reflect that it is not just individuals who invent their own past and tell lies, but that powerful organisations do it as well.

12. Are there any new authors that have sparked your interest? I have just finished reading an excellent debut historical novel The Lady’s Slipper by Deborah Swift. Set in 1660, it is about a rare orchid which rips a community apart as various people try to get it for their own ends. I am halfway through a very gripping modern thriller The Woman Before Me, also by a debut novelist. This is a modern psychological thriller about a woman accused of an arson attack in which a baby has died. She tries to convince a probation officer she is safe to be let out of prison, but is the probation officer being drawn into a dangerous deceit? Not a new book, but one of my favourite spine-chillers is Sarah Rayne’s Spider light. It’s set both in modern and Victorian times, and is about a modern woman who flees for her safety to remote cottage and discovers nearby the ruins of a mental hospital with a dark and terrifying part. Gradually these two worlds come together. I made the mistake of reading this book alone at night in a storm in a remote cottage on the marshes, where I had gone to write because the cottage has no phone, no email and no mobile reception. Spider light is so dark and atmospheric that I found myself jumping at every creak and rustle in the night.

13. Do you have any other projects you're currently working on? My new medieval thriller, The Gallows Curse, is due out in UK in the spring. It is set in England in 1210, when the whole of England was excommunicated for a period of six years. One of the two main characters is an Italian castrato, Raffaele, who fought in the Crusades, but has come to England as steward to an English knight. The knight is dying unshriven, because no priest can be found to absolve him, but he has committed a terrible sin which he has never confessed. Raffaele rashly swears that he will somehow remove this sin from his beloved friend’s soul, a desperate oath in which the innocent get caught up in disaster and murder. Right now I am currently racing to finish another full-length novel The Falcons of Fire and Ice which is set in 1564 in Portugal and Iceland. It was terrible year in which Marranos, Muslims and Lutherans were being tortured and burned by the Inquisition in Portugal, while in Iceland Catholics were being persecuted and murdered during the Reformation. I am also trying to think up a plot for my novella in the next joint Medieval Murderers novel.

14. Thank you so much. It was a real pleasure for me. Do you have something to tell before you say goodbye? I wanted to say how thrilled I am that my novel has been translated into Italian. Whenever I come to Italy on holiday, it always feels as if I am coming home, probably because I spent my early childhood in Malta and there are so many similarities in architecture and culture. I can’t wait to come back to Italy again, as no matter which part I’ve visited I’ve always had a fantastic time. Thank you so much for reading this blog interview and giving me the chance to share some thoughts with you. And thank you too for the reading Company of Liars. I do hope you enjoyed it. ed into Italian. Whenever I come to Italy on holiday, it always feels as if I am coming home, probably because I spent my early childhood in Malta and there are so many similarities in architecture and culture. I can’t wait to come back to Italy again, as no matter which part I’ve visited I’ve always had a fantastic time. Thank you.