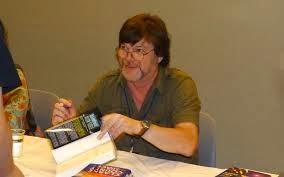

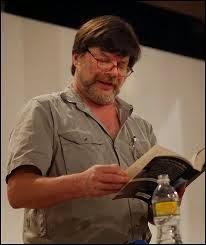

L'intervista di oggi è dedicata al grande Allen Steele, uno dei maggiori scrittori di fantascienza contemporanei.

L'intervista di oggi è dedicata al grande Allen Steele, uno dei maggiori scrittori di fantascienza contemporanei.Di Steele, ultimamente sto apprezzando molto il ciclo di Coyote, che sto leggendo in lingua originale.

Ancora una volta posso testimoniare di avere incontrato una persona estremamente gentile ed innamorata del suo lavoro. Come sempre avrei voluto fare un centinaio di altre domande ad Allen Steele, ma in quel caso non sarebbero bastate trenta pagine a raccoglierle tutte quante. Spero attraverso le domande fatte di essere riuscito a fare comunque un buon lavoro.

Ringrazio di vero cuore Allen Steele per tutto quanto, mentre a voi auguro una buona lettura.

Come sempre, eventuali errori o imprecisioni vanno addebbitate esclusivamente alla mia persona.

(For english version scroll down )

Nick: Ciao Allen, grazie per aver accettato quest'intervista. Quando hai deciso di cominciare a scrivere e quali sono stati i tuoi inizi?

Allen Steele: Ho scritto la mia prima storia ai tempi della scuola elementare, sotto forma di un compito che il mio insegnante ha dato a tutta la classe. Lui ha distribuito delle foto prese da varie riviste e ci ha detto di scrivere racconti ispirati da queste immagini. L'immagine che ha dato a me ritraeva una famiglia in una macchina volante, un tipico esempio di immagine futuristica degli anni 60 s. Ho scritto la storia e ho scoperto che mi piaceva farlo ( e dato che io veramente li odiavo i compiti i compiti a casa, questo la dice lunga in proposito , così la scrittura è diventato una specie di hobby per me fino a quando ho compiuto 15 anni, allora ho capito che questo era ciò che ho voluto fare della mia vita ... diventare un autore di fantascienza .

Nick: Nei tuoi romanzi omaggi spesso due autori in particolare: Arthur C. Clarke e Robert A. Heinlen, di cui sei chiaramente fan. Cosa ti ha appassionato in particolare della loro opera? E a parte loro due quali sono stati gli scrittori che ti hanno formato maggiormente? Naturalmente puoi citare anche film, serie tv, fumetti.

Allen: Anche prima di essere colpito dal bug della scrittura, ero un enorme appassionato dello Spazio . Sono cresciuto guardando le missioni Mercury, Gemini e Apollo, possedevo un enorme collezione di giocattoli spaziali e di modellini, ti potrei dire in dettaglio come funzionavano tutte quelle navicelle e dove erano posizionati gli astronauti. Così, quando ho cominciato a leggere, ho cominciato a gravitare in maniera naturale verso la fantascienza , e i libri e le storie che consideravo migliori erano quelli che trattavano l'esplorazione dello spazio. Clarke e Heinlein erano i migliori sotto questo punto di vista, così è avvenuto in maniera naturale che il loro lavoro sia poi diventato una grande fonte d' influenza per me , ma altri che mi hanno influenzato sono stati Jules Verne, Isaac Asimov e Frederik Pohl. E poi ci sono stati molti spettacoli televisivi e film : Lost in Space è stato il mio primo amore ( quantomeno la prima stagione, prima che diventasse così stupido che perfino i ragazzini smettessero di crederci ) e anche la serie originale di Star Trek , così come film quali Abbandonati Nello Spazio ( Marooned ) , Destinazione Luna (Destination Moon), Base Luna Chiama Terra ( The First Men in the Moon ) , e il più grande di tutti, 2001: Odissea nello spazio .

Nick: La tua è una fantascienza classica in cui echeggia molto spesso il richiamo della frontiera, della lotta contro la tirannia e della fuga degli individui per difendere le proprie libertà individuali Quando è nato- e perché- dentro di te l'interesse per queste tematiche?

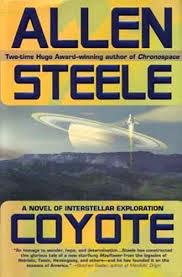

Nick: La tua è una fantascienza classica in cui echeggia molto spesso il richiamo della frontiera, della lotta contro la tirannia e della fuga degli individui per difendere le proprie libertà individuali Quando è nato- e perché- dentro di te l'interesse per queste tematiche?Allen: Sono nato e cresciuto nel Sud degli Stati Uniti, il che vuole dire che sono cresciuto sapendo tutto sulla Guerra Civile. In realtà, il mio bisnonno è stato un ufficiale dell'esercito confederato. Ad oggi, però, condivido gli stessi sentimenti contrastanti che molti abitanti del Sud hanno su quella guerra: ammiriamo gli uomini che hanno combattuto, eppure consideriamo sbagliate le loro ragioni per farlo e sappiamo che quelle idee non possono essere difese. E 'qualcosa che ogni discendente di un soldato Confederato ha dovuto affrontare, e penso che questa dissonanza ha trovato la sua strada nella mia narrativa, quando ho scritto riguardo gli stessi argomenti. Adesso vivo in New England, dove ho trascorso la maggior parte della mia vita adulta, e qui mi trovo a vivere sul campo di battaglia di altre guerre: la Rivoluzione Americana, e prima ancora, La Guerra di Re Filippo ,* un conflitto in gran parte dimenticato in cui il primi coloni hanno dovuto affrontare una rivolta sanguinosa da parte dei nativi americani causata dal risentimento verso gli europei che stavano arrivando nella loro terra. Quindi, questi conflitti hanno avuto un influenza sul mio lavoro e ... in particolare, la hanno avuta sui romanzi del ciclo di Coyote .

Nick: Possiamo dire che è come se tu, nei tuoi scritti, avessi trasportato il Mito americano della Frontiera e Far West nello Spazio?

Allen: Un sacco di lettori credono che lo scenario del West americano fornisca la base storica per i miei romanzi, ma il periodo pre- Guerra d'Indipendenza della storia americana mi ha influenzato molto di più della Conquista del West. Sulle colline del piccolo paese dove abito si trovano ancora i resti di case e fattorie che sono state costruite molto tempo prima che avvenisse l'espansione verso ovest, e nei musei vi sono reliquie del modo in cui queste persone vivevano. Ho visitato questi luoghi, mentre mi documentavo e mentre scrivevo Coyote e i suoi seguiti, e mi hanno fornito una buona idea di cosa potrebbe voler dire trovarsi a vivere fuori dalla Terra in un mondo nuovo. Ma appena la serie si è sviluppata e ho cominciato a scrivere di insediamenti più grandi con più abitanti, ho iniziato a studiare la storia del Vecchio West, che ha trovato il suo posto nei libri successivi .

Nick: I tuoi protagonisti sono quasi sempre persone comuni, che descrivi con gran simpatia, spesso li descrivi come uomini comuni, magari dotati di solide convinzioni personali ma di certo non superuomini.Lo stesso vale per i tuoi cattivi, spesso ho la sensazione che che i tuoi antagonisti non siano persone realmente malvagie, ma individui in buona fede che hanno solo fatto scelte sbagliate o che agiscano credendo di essere dalla parte giusta, un po come se tu volessi dire che tutti possiamo nel corso delle nostre azioni ritrovarci dalla parte sbagliata per nostra sola responsabilità. E' una ricostruzione sbagliata la mia? E Come mai questa scelta?

Allen: Penso che tu abbia ragione. Io non sono interessato a scrivere di supereroi. I personaggi archetipici che non possono sbagliare e che superano tutte le situazioni senza nemmeno un graffio non sono solo irrealistici, ma sono anche noiosi. Sono molto più attratto verso gli uomini e le donne comuni che si trovano in situazioni straordinarie e che devono capire come affrontarle. I personaggi nelle mie storie non sono action figures. Hanno difetti, e avolte possono sbagliare e convivere con le conseguenze delle loro azioni.

Allen: Penso che tu abbia ragione. Io non sono interessato a scrivere di supereroi. I personaggi archetipici che non possono sbagliare e che superano tutte le situazioni senza nemmeno un graffio non sono solo irrealistici, ma sono anche noiosi. Sono molto più attratto verso gli uomini e le donne comuni che si trovano in situazioni straordinarie e che devono capire come affrontarle. I personaggi nelle mie storie non sono action figures. Hanno difetti, e avolte possono sbagliare e convivere con le conseguenze delle loro azioni. Per la stessa ragione, io scrivo molto raramente di persone che siano palesemente malvagie. La mia esperienza al riguardo è stata che le persone che fanno cose cattive, spesso lo fanno perché loro stesse si sono trovate dalla parte sbagliata di una situazione e stanno cercando di fare quella che ritengono sia la cosa giusta pur essendo a conoscenza dei danni che stanno causando. Le persone raramente tendono a considerasi come cattive, nelle loro menti, anzi si considerano eroi, e semplicemente non si rendono conto che questo non è sempre vero.

Nick: Nel 1989 scrivi il tuo primo romanzo Orbita Olympus ( Orbital Decay) con cui dai inizio al ciclo conosciuto come Spazio Vicino (Near Space.) Vorrei che tu tornassi per noi con la memoria ai momenti e alle sensazioni che provavi mentre scrivevi il tuo primo libro, e anche alle eventuali difficoltà. Sopratutto m'interessa sapere se avevi già intenzione di trasformare il romanzo in un ciclo?

Allen: Orbita Olympus è stato il secondo romanzo che ho scritto - il primo è stato un thriller tradizionale che per fortuna non è mai stato pubblicato - avevo deciso di scrivere un romanzo realistico riguardo l'esplorazione dello Spazio. All'epoca, la maggior parte della SF ambientata nello Spazio veniva ambientata lontano nella galassia e popolata da quel tipo di personaggi di stampo eroico di cui ho appena parlato. I film di Star Wars e Star Trek: The Next Generation avevano questa enorme influenza sul genere da cui io volevo molto consapevolmente ribellarmi. Così ho scritto esattamente la cosa opposta: di uomini che lavorano come operai nello spazio, con l'orbita terrestre e la Luna come sfondo, e come antagonisti non alieni malvagi o qualche Bad Guy Empire , ma piuttosto la propria azienda e la National Security Agency. Quando alla fine dell'anno scorso Orbita Olympus è stato ristampato sotto forma di ebook, diversi lettori hanno notato che avevo presagito con anticipo la sorveglianza globale elettronica praticata in tempi recenti dalla NSA. Ne sono anche rimasto un po sorpreso, ma decisamente non troppo sorpreso. La capacità tecnologica esiste da un bel po ' ... io ne solo estrapolato le possibili conseguenze .

Ho iniziato a scrivere Orbita Olympus mentre mi stavo laureando in giornalismo e l'ho finito mentre lavoravo come staff reporter per un giornale settimanale dell' area alternativa. Il primo editore a cui l' ho presentato respinse il libro proprio perché era diverso da quello che circolava all'epoca, l'editor che lo valutò negativamente era deluso dal fatto il libro non presentava alieni, battaglie tra astronavi, e cose simili . Ma in seguito fortunatamente Ginjer Buchanan, l'editor di un altra casa editrice, la Ace, percepì che il libro era diverso dalla maggior parte di ciò che veniva pubblicato in quel momento, e il libro divenne un successo proprio a causa di questa differenza .

Ho iniziato a scrivere Orbita Olympus mentre mi stavo laureando in giornalismo e l'ho finito mentre lavoravo come staff reporter per un giornale settimanale dell' area alternativa. Il primo editore a cui l' ho presentato respinse il libro proprio perché era diverso da quello che circolava all'epoca, l'editor che lo valutò negativamente era deluso dal fatto il libro non presentava alieni, battaglie tra astronavi, e cose simili . Ma in seguito fortunatamente Ginjer Buchanan, l'editor di un altra casa editrice, la Ace, percepì che il libro era diverso dalla maggior parte di ciò che veniva pubblicato in quel momento, e il libro divenne un successo proprio a causa di questa differenza .Orbita Olympus é stato originariamente pensato per essere un romanzo stand- alone, ma dopo averlo terminato avevo finito, mi sono reso conto di non avere detto tutto quello che avrei voluto dire sull'argomento, così ho continuato a scrivere altri racconti e altri romanzi con lo stesso sfondo, che alla fine si è trasformato nella serie del Near Space. Di tanto in tanto mi dedico ancora a scrivere storie del Near Space, anche se Orbita Olympus viene considerato ormai piuttosto datato ( a parte la roba sulla NSA ). Più o meno la stessa cosa mi è accaduta di nuovo anni dopo, quando ho scritto Coyote . Ancora una volta, il tutto è stato concepito per essere solo un libro, ma quando ho raggiunto la fine , mi sono reso conto che la storia che volevo raccontare ancora non era finita, così ho continuato ad andare avanti sull'argomento finché non sono diventati ... quattro romanzi , tre spin-off , e una mezza dozzina di opere short -fiction successive .

Nick: Uno dei tuo romanzi che mi è piaciuto di più è Nel Labirinto della Notte. Però da come ne parli spesso sembra che sia stato quello che ti ha creato più problemi a causa dell'utilizzo della "Faccia di Marte", è vero?

Allen: Nel Labirinto della Notte è stato scritto come una storia di avventura che si colloca appieno nel ciclo dello Spazio Vicino ed ho utilizzato la cosiddetta "Faccia di Marte" come il suo trampolino di lancio. Quando ho iniziato a scrivere il romanzo, il "Volto" era un qualcosa che conoscevano relativamente poche persone, io non ho mai preso sul serio, ma ho semplicemente pensato che fosse una interessante anomalia che sarebbe potuta divenire una buona base per un romanzo di Primo Contatto. Ma il libro ha avuto una lunga genesi - ad un certo punto l'ho anche messo da parte per un paio di anni per scrivere invece altri due romanzi - così quando è arrivato il momento in cui il libro è stato finito e pubblicato, il "Volto" era diventato molto noto al pubblico e, a mia insaputa, era cresciuto attorno ad esso una sorta di culto o di teoria della cospirazione. Così alcuni tra i lettori hanno pensato che io detenessi chissà quale conoscenza segreta sulla "Faccia" e che la stavo divulgando nel contesto di un romanzo di fantascienza, e questo nonostante io avessi avuto la cautela di affermare nella premessa al romanzo di non credere assolutamente nell'esistenza della "Faccia", o almeno di non credere che si tratti di un manufatto extraterrestre **. Ho dovuto spendere un sacco di tempo per spiegare pazientemente come stavano le cose.

In seguito ho scritto un paio di belle storie del ciclo del Near Space ambientate su Marte, ma da allora, ho scelto di ignorare semplicemente la "Faccia" o gli eventi di Nel Labirinto della Notte.

Ritengo che il romanzo sia piuttosto buono e che regga bene come storia di avventura.

Il romanzo è stato recentemente ristampato in ebook e spero che alla gente piaccia, ma spero anche che non lo prendano troppo sul serio.

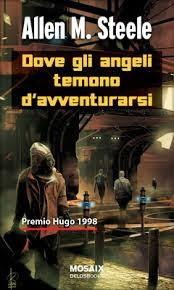

Nick: Hai vinto per ben tre volte il Premio Hugo: nel 1996 con "La Morte di Capitan Futuro"; nel 1998 con"... Dove gli Angeli temono di'Avventurarsi" e nel 2011 con "L'Imperatore di Marte". Cosa ha significato per te la vittoria di un premio così importante, specialmente perchè sappiamo che ci tenevi tanto a vincerlo e quanto pensi in generale, che possa influire nell'attività di uno scrittore la vincita di premio così importante?

Allen: La vittoria di quel primo Hugo per " La Morte di Capitan Futuro " ha rappresentato la realizzazione dei sogni di tutta una vita. Quando da adolescente ho deciso di diventare uno scrittore, quello che desideravo di più era vincere un Premio Hugo. Da allora ne ho vinto anche altri due, inoltre ho ottenuto anche altre cinque nomination, e questo mi ha fatto comprendere il vero significato di che cosa rappresenti questo premio: i lettori danno il premio alla storia, non all' autore, e se ti capita di vincerne uno, significa che il tuo lavoro ha superato lo scoglio con uno dei pubblici più esigenti al mondo. Io potrei non vincere mai più un altro Hugo - anche se mi auguro di farlo - ma il fatto di possederne tre sulla libreria del mio salotto mi incoraggia a fare il miglior lavoro possibile.

Allen: La vittoria di quel primo Hugo per " La Morte di Capitan Futuro " ha rappresentato la realizzazione dei sogni di tutta una vita. Quando da adolescente ho deciso di diventare uno scrittore, quello che desideravo di più era vincere un Premio Hugo. Da allora ne ho vinto anche altri due, inoltre ho ottenuto anche altre cinque nomination, e questo mi ha fatto comprendere il vero significato di che cosa rappresenti questo premio: i lettori danno il premio alla storia, non all' autore, e se ti capita di vincerne uno, significa che il tuo lavoro ha superato lo scoglio con uno dei pubblici più esigenti al mondo. Io potrei non vincere mai più un altro Hugo - anche se mi auguro di farlo - ma il fatto di possederne tre sulla libreria del mio salotto mi incoraggia a fare il miglior lavoro possibile.Nick: Sbaglio o "La Morte di Capitan Futuro" è stato adattato per una trasmissione radiofonica?

Allen: Un ottimo adattamento audio de "La Morte di Capitan Futuro " è stato realizzato molti anni fa, per l'attualmente defunto sito web Seeing Ear Theater di Sci- Fi Channel. Ho scritto la sceneggiatura assieme con il produttore, e poi è venuto fuori su nastro e so che è ancora disponibile online. Sono molto contento del risultato finale, e vorrei poter avere l' opportunità di fare qualcosa di simile in futuro.

Nick: Sei universalmente definito come uno scrittore di "Hard Science Fiction", ti ritrovi in questa descrizione o la ritieni riduttiva ? E nel caso come definiresti le tue opere?

Allen: "Fantascienza Hard" è un marchio che è stato appiccicato molto presto sul mio lavoro e ho imparato a conviverci, ma in realtà io mi considero uno scrittore di fantascienza, e basta. Qualcuno una volta ha chiesto ad uno dei miei artisti preferiti, Miles Davis, le sue sensazioni sul jazz, e lui per tutta risposta ha negato di essere un musicista jazz ... dichiarando di considerarsi semplicemente un musicista e basta. Questa è la modalità con cui mi rapporto al mio lavoro ...io scrivo fantascienza , e il termine "hard" è solo la descrizione data da qualcun altro per quello che faccio .

Allen Steele e i suoi Hugo

Nick: Tu fai parte del Consiglio di consulenti per la "Space Frontier Foundation", puoi dirci qualcosa di questa esperienza?

Allen: Si, faccio parte del comitato consultivo della "Space Frontier Foundation" e sono molto orgoglioso di farlo, io sostengo pienamente la loro agenda, che sta promuovendo e sostenendo l'esplorazione privata dello Spazio. Ma loro molto raramente entrano in contatto con me, quindi è diventato una sorta di carica onoraria .

Nick: Cosa ne pensi degli attuali programmi di esplorazione spaziale? Pensi che siano adeguati o si dovrebbe osare di più (magari con un maggiore sostegno e più fondi da parte dei governi e dei cittadini)?

Allen : Questo è un periodo molto interessante per l'esplorazione dello Spazio. Assistiamo allo stesso tempo al principio della scomparsa dei grandi programmi spaziali sostenuti dai governi, come la NASA, e questo è dovuto in gran parte ai finanziamenti irrisori e alla mancanza di obiettivi governativi a lungo termine, mentre aziende private come Space - X, Orbital Sciences, Virgin Galactic e Bigelow Space stanno entrando nel settore con le proprie forze costruendo e lanciando la propria astronave. Per ora , i loro sforzi sono alquanto su piccola scala, ma le loro ambizioni sono molto vaste, e stanno avvalendosi delle competenze non solo dei veterani della NASA, ma anche da parte di scienziati e ingegneri più giovani - gruppo che ho cominciato a chiamare " Generation Star Trek " perché sono ispirati dalla stessa fantascienza che ha ispirato me. Alcune di queste persone mi hanno riferito di essere stati ispirati anche dal mio lavoro, il che mi rende davvero molto orgoglioso.

Quindi ci stiamo avvicinando verso un luogo in cui la mancanza di fondi da parte dei contribuenti è piuttosto discutibile. Le società americane che stanno facendo questo genere di cose lo stanno facendo per fare soldi, e anche se sono ancora dipendenti dai siti di lancio della NASA, i loro obiettivi a lungo raggio sono indipendenti da gli obiettivi che può avere un governo piuttosto volubile e che non può vedere al di là delle prossime elezioni. Il tipo di futuro che ho descritto circa 25 anni fa in Orbita Olympus si sta avverando più lentamente di quanto immaginassi - purtroppo,-non ci stiamo preparando ad avere satelliti a energia solare e basi lunari industriale entro il 2016 - ma siamo sulla buona strada. Il passato è solo il preludio, e ora siamo sull'orlo di una vero e propria Era Spaziale .

Nick: Leggi ancora le opere dei tuoi colleghi, e se si quali ti piacciono di più?

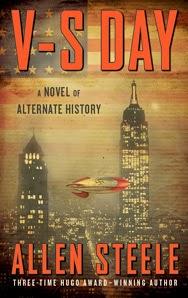

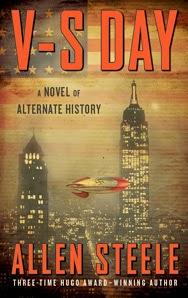

Nick: Il tuo nuovo romanzo, "V-S Day" sta affrontando il mercato in questo momento. Puoi presentare questo progetto ai tuoi lettori italiani?

Allen: "V-S Day" è un romanzo di storia alternativa - è il racconto di quello che sarebbe potuto accadere se la corsa allo Spazio fosse nata durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale, sotto forma di una competizione segreta tra gli Stati Uniti e la Germania nazista per mandare una nave spaziale fornita di equipaggio militare in orbita. L'ispirazione mi è venuta da una proposta fatta realmente dal fisico austriaco Eugen Sanger per una navetta spaziale orbitale, il Silbervogel, che avrebbe dovuto bombardare New York City; nel mio romanzo, l' Intelligence britannica fa tesoro dei suggerimenti e dei segreti americani, riuscendo ad ottenere l'aiuto di Robert H. Goddard, l'inventore del razzo a propellente liquido, che viene messo a capo di un programma accelerato per sviluppare un deterrente ai bombardamenti .

Mi sono divertito parecchio durante le fasi di ricerca e di scrittura del libro. In origine lo avevo scritto sotto forma di un racconto, "Goddard's People, uno dei miei primi lavori pubblicati, più tardi divenne una sceneggiatura per un film che non fu mai realizzato. Questa volta, sono stato in grado di espandere la storia considerevolmente, e di aggiungere un sacco di materiale che prima non c'era C'è un capitolo che si svolge a Parigi , per esempio, di cui io sono particolarmente orgoglioso ... Sono andato in Francia per svolgere delle ricerche, e così visitato la Cattedrale di Notre Dame e camminato per le strade della Rive Gauche per raccoglierne i giusti dettagli.

Questo è il genere di cose che rendono lo scrivere così divertente.

Nick: Progetti futuri: a cosa stai lavorando e cosa ci dobbiamo aspettare da Allen Steele nel prossimo futuro?

Allen: Attualmente sto scrivendo una serie di racconti - in realtà, si tratta più che altro di romanzi brevi - per la rivista Asimov's Science Fiction, che descrivono un tentativo lungo diverse generazioni per costruire e lanciare la prima nave stellare. La linea temporale si estende dal 1939 al 25 ° secolo , e presenta un approccio diverso per l'esplorazione interstellare rispetto alla serie di Coyote. La prima storia, "The Legion of Tomorrow ", apparirà in America nel numero di luglio. La seconda storia, "The Prodigal Son", è appena stata venduto e apparirà qualche tempo dopo nel corso dell'anno, mentre sto ora lavorando al terzo racconto, "The Long Wait".

C'è anche un lungo saggio, "Tomorrow Through The Past", che, apparirà quest'anno in Asimov's . Si tratta di una valutazione dello stato attuale della fantascienza - " il buono, il brutto e il cattivo", per prendere in prestito il titolo da uno dei miei Spaghetti Western preferiti - il saggio non è altro che un ampliamento del discorso che ho pronunciato come Ospite d'onore alla convention di fantascienza Philcon alla fine dell'anno scorso. Credo che alcune delle cose che ho scritto possano essere ritenute controverse, dovremo vedere quale sarà la reazione. Ed è davvero sempre così.

Io scrivo le cose e le metto a disposizione, e poi la risposta che arriva dai miei lettori è sempre un qualcosa di interessante

Nick: Bene Allen con questo abbiamo finito, nel salutarti ti rivolgo la classica domanda finale di Nocturnia: c'è una domanda alla quale avresti risposto volentieri e che io invece non ti ho rivolto?

Allen: Non riesco a pensare a niente altro, davvero. Ancora una volta , ti ringrazio per avermi invitato a fare questa intervista. Grandi domande - sono stato felice di rispondere a tutte quante loro!

NOTE:

* Sanguinoso conflitto avvenuto tra il 1575 e il 1676 e che fu combattuto tra coloni inglesi e alcune tribù a loro alleate contro il resto delle tribù indiane del New England. Il conflitto viene così chiamato dal nome del più importante capo indiano dell'epoca, Capo Metacom, chiamato dagli inglesi Re Filippo. La guerra inizialmente vide trionfare i nativi ma dopo qualche mese i coloni, più organizzati ebbero la meglio.

Il conflitto si rivelò una strage da entrambe le parti: si calcola che almeno uno su venti tra gli abitanti del New England, non importa se europeo o nativo americano, perse la vita durante quella guerra.

** l'introduzione in questione è presente anche nell'edizione italiana di Nel Labirinto della Notte pubblicata da Fanucci

INTERVIEW WITH ALLEN STEELE! - THE ENGLISH VERSION.

I would like to thank Mr. Steele for his availability, his kindness and for the wonderful chat.

To all of you readers I hope you enjoy reading!

Nick: Hello Allen, thank you for accepting this interview. When you have decided to start writing and what were your beginnings ?

Allen Steele: I wrote my first story when I was in elementary school, as an assignment my teacher gave the class. She handed out pictures she'd taken from magazines and told us to write short stories about them. The picture she gave me was an illustration of a family in a flying car, a very 60's-style futuristic image. I wrote the story and discovered that I liked doing it (and since I really hated homework, this says a lot in itself), so writing became something of a hobby for me until I was 15 years old, when I realized that this was what I wanted to do with my life ... become a science fiction author.

Nick: In your novels you gift often two authors in particular: Arthur C. Clarke and Robert A. Heinlen , of which you are clearly a fan . What has particularly fond of their work ? And aside from the two of them what were the writers that have formed the most? Of course you can also mention movies , TV series, comics.

Steele: Even before I got bitten by the writing bug, I was huge space buff. I grew up watching the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions, had an enormous collection of space toys and models, and could tell you in detail how spacecraft worked and who the astronauts were. So when I began reading, naturally I gravitated toward science fiction, and the books and stories I liked the best were those which those which dealt with space exploration. Clarke and Heinlein were the best at this, so of course their work would eventually become a great influence, but others who affected me were Jules Verne, Isaac Asimov, and Frederik Pohl. And there were many TV shows and movies: Lost in Space was my first love (the first season, at least, before it became so silly that even a little kid couldn't believe it) and the original Star Trek, as well as films like Marooned, Destination Moon, The First Men in the Moon, and the greatest of them all, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Nick: Yours is a classic science fiction that often echoes the call of the frontier in the fight against tyranny and the escape of persons to protect their individual freedoms When it was born - and why - in you the interest about these issues ?

Steele: I was born and raised in the South, so I grew up knowing all about the Civil War. In fact, my great-grandfather was an officer in the Confederate Army. To this day, though, I share the same conflicted feelings many southerners do about that war: we admire the men who fought it, yet their reasons for doing so were wrong and can't be defended. It's something that every Confederate descendent has had to grapple with, and I think this dissonance has found its way into my fiction when I've written about the same sort of thing.

I now live in New England, where I've spent most of my adult life, and here I find myself living on the battleground of other wars: the Revolutionary War, and before that, King Philip's War, a largely forgotten conflict in which the early settlers had to deal with a bloody uprising by the Native Americans who'd become resentful of the Europeans who'd come to their land. So these conflicts have had an influence on my work as well ... in particular, the Coyote novels.

Nick: we can say that it is as if you, in your writings , have carried the Myth of the American Wild West and Frontier in Space ?

Steele: A lot of readers believe the settlement of the American West is the historical basis for my novels, but the pre-Revolutionary War period of American history has influenced me much more than the taming of the west. Up in the hills of the small town where I live are the remains of houses and farms that were built long before the westward expansion, and in the museums are relics of the way they lived. I visited these places while I was researching and writing Coyote and its subsequent stories, and they gave me a good idea of what it's like to have to live off the land in a new world. But as the series went on and I began writing about larger settlements with more inhabitants, I began studying the history of the Old West, and that found its way into the later books.

Nick: Your protagonists are almost always ordinary people who describe with great sympathy, often describe them as ordinary men , perhaps with strong personal convictions but certainly not supermen. The same goes for your bad ones , I often get the feeling that your opponents are not really bad people , but people in good faith that just made bad choices or believing they are acting on the right side , a little as if you wanted to say that we can all find ourselves in the course of our actions on the wrong side for our sole responsibility. Is that reconstruction wrong ? And Why this choice ?

Steele: I think you have it right. I'm not interested in writing about superheros. Archetypical characters who can do no wrong and get out of situations unscratched aren't just unrealistic; they're also boring. I'm much more drawn toward ordinary men and women who finds themselves in extraordinary situations and have to figure out how to cope with them. The people in my stories aren't action figures. They have faults, and they sometimes make mistakes and have to live with the consequences. And by much the same token, I very seldom write about people who are manifestly evil. My experience has been that people who do bad things often do so because they've found themselves on the wrong side of a situation and are trying to do the right thing while being unaware of the harm they're causing. People seldom set out to become villains; in their own minds, they're heroes, and just don't realize that this isn't true.

Nick: In 1989 write your first novel Orbital Decay with which you start the cycle known as Near Space. I wish you'd come back to us with the memory to the moments and the feelings you felt when you wrote your first book , and the difficulties too. Above all I'm interested to know if you already had plans to transform the novel into a loop?

Steele: Orbital Decay was the second novel I wrote -- the first was a mainstream thriller that thankfully was never published -- and I set out to write a realistic novel about space exploration. At the time, most SF about space was set far out in the galaxy, with characters in the heroic mold I just spoke about. The Star Wars movies and Star Trek: The Next Generation had this enormous influence on the genre that I was very consciously rebelling against. So I wrote about the exact opposite thing: blue-collar working men in space, with Earth orbit and the Moon as the setting, and antagonists not being evil aliens or some Bad Guy Empire, but rather their own company and the National Security Agency. When Orbital Decay was reissued late last year as an ebook, quite a few readers noticed that I'd presaged NSA electronic global surveillance. I was kind of surprised, too, but not very much. The technological capability has existed for quite a while ... I just had to extrapolate the possible consequences.

I started writing Orbital Decay while I was in journalism grad school and finished while I was working as a staff reporter for a weekly alternative newspaper. The first publisher to whom I submitted it rejected the book precisely because it was different from what was already out there; the editor who turned it down was disappointed that it didn't have aliens, spaceship battles, and the like. But Ace's editor, Ginjer Buchanan, perceived that it was different from most of what was being done at the time, and book became a success because of that difference.

Orbital Decay was originally meant to be a stand-alone novel, but after I finished it, I realized that I hadn't said everything on the subject that I wanted to say, so I continued writing more stories and novels with the same background, and they eventually became the Near Space series. I'm still occasionally writing Near-Space stories even though Orbital Decay itself is now rather dated (the NSA stuff notwithstanding). Much the same thing happened again years later when I wrote Coyote. Again, it was meant to be just one book, but when I reached the end, I realized that the story I wanted to tell still wasn't finished, so I kept going until it was ... four novels, three spin-offs, and a half-dozen short-fiction works later.

Nick: One of your novels that I liked most is Labyrinth of Night. But to talk as often seems to have been the one who created you more problems due to the use of the " Face on Mars ", is not it?

Steele: Labyrinth of Night was written as an adventure story taking place in the Near Space series that used the so-called Face on Mars as its springboard. When I first started to write it, the Face was something relatively few people knew about; I never took it seriously, but simply thought that it was interesting anomaly that would be a good basis for a first-contact novel. But the book had a long genesis -- at one point I put it aside for a couple of years and wrote two other novels instead -- so by the time it was finished and published, the Face had become very well known to the public and, unbeknownst to me, a sort of conspiracy-theory cult had grown up around it. So some who read it thought that I had some secret knowledge about the Face that I was divulging within the context of a SF novel, even though I carefully stated in the foreword that I didn't believe that the Face really existed, or at least not as an extraterrestrial artifact. I've had to spend a lot of time patiently explaining otherwise.

I've written quite a few Near-Space stories set on Mars since then, but I've chosen to simply ignore the Face or the events of Labyrinth of Night. I think the novel is pretty good and that it holds up well as an adventure story. The novel has recently been released again as an ebook and I hope people like it, but I also hope they don't take it too seriously.

Nick: You won the Hugo Award three times : in 1996 with " The Death of Captain Future " in 1998 with " Where Angels Fear to Tread " and in 2011 with "The Emperor of Mars" . What did it mean to you to win a so important award , especially because we know that you cared so much to win and how much do you think in general that may affect the activity of a writer to win the prize so important?

Steele : Receiving that first Hugo for "The Death of Captain Future" was the fulfillment of a lifelong ambition. When I decided to become a writer as a teenager, that was what I wanted the most: win a Hugo Award. I've won two more since then, and have had five other nominations besides, and I've learned what this award is really about: the readers give the award to the story, not the author, and if you happen to win one, it means that your work has passed muster with one of the toughest audiences in the world. I may never win another Hugo -- although I certainly hope I do -- but the fact that I have three on my living room bookcase encourages me to do the best work I possibly can.

Nick: Am I wrong or " The Death of Captain Future " has been adapted for a radio broadcast?

Steele : A very good audio adaptation of the "The Death of Captain Future" was done many years ago for the Sci-Fi Channel's now-defunct Seeing Ear Theater web site. I co-wrote the script with the producer, and it later came out on tape and I understand it's still available online. I'm very happy with the way it came out, and I wish I had the opportunity to do something like that again.

Steele : "Hard science fiction" is a label that was put on my work very early and I've learned to live with it, but really I consider myself to be a science fiction writer, period. Someone once asked one of my favorite artists, Miles Davis, about how he felt about jazz, and he denied being a jazz musician ... he said that he was simply a musician and that was it. That's sort of how I approach my work ... I write science fiction, and the "hard" bit is someone else's description for what I do.

Nick: you're on the board of advisors for the "Space Frontier Foundation", can you tell us anything about this experience?

Steele: I'm on the advisory board for the Space Frontier Foundation and very proud to be there; I fully support their agenda, which is promoting and supporting the private exploration of space. But they're very seldom in touch with me, so it's become something of an honorary position.

Nick: What do you think of today's space exploration programs , do you think are appropriate or should be more daring (perhaps with more support and more funding from governments and citizens )?

Steele: This is a very interesting period in space exploration. At the same time that big, government-supported space programs like NASA are beginning to fade, largely due to paltry funding and lack of long-term government objectives, private companies like Space-X, Orbital Sciences, Virgin Galactic, and Bigelow Space are coming into their own by building and launching their own spacecraft. For now, their efforts are rather small-scale, but their ambitions are vast, and they're drawing upon the expertise of not only NASA veterans but also younger scientists and engineers -- the group I've come to call "Generation Star Trek" because they're inspired by the same science fiction that inspired me. I've even had some of them tell me that they've been inspired by my work, which makes me very proud indeed.

So we're approaching a place where lack of taxpayer funding is rather moot. The American companies who are doing this sort of thing are in it to make money, and although they're still dependent on NASA launch sites, their long-range goals are independent of a rather fickle government that can't see beyond the next election. The kind of future I wrote about 25 years ago in Orbital Decay is occurring more slowly than I imagined -- regretfully, we're not going to have solar power satellites and industrial moon bases by 2016 -- but it's on the way. The past is prelude, and now we're on the verge of a real Space Age.

Nick: Read again the works of your colleagues , and if so what do you like more ?

Steele: I still read SF, although not as much as I used to; I also read mysteries and books about American history and current politics. That said, I enjoy novels and stories by the older generation of writers who are still practicing, like Gregory Benford, Larry Niven, and Jack McDevitt, and writers who came on the scene about the same time I did, like Robert J. Sawyer, Kristine Katherine Rusch, and Stephen Baxter, and the newest crop of writers, like James Cambias, Lavie Tidhar, and Jamie Todd Rubin. And now that I'm safely in my middle-age. I'm able to re-read the novels I enoyed when I was younger as if they're new books because I've forgotten what they were about. So I just read 2001: A Space Odyssey for the first time since I was a kid, and liked it even better the second time around.

Nick: Your new novel, "V-S Day " is hitting the market right now. Can you present this project to your italian readers?

Steele: V-S Day is an alternate-history novel about what might have happened if the Space Race had occurred during World War II, as a secret competition between the U.S. and Nazi Germany to put manned military spacecraft into orbit. The inspiration came from a real-life proposal by the Austrian physicist Eugen Sanger for an orbital spaceplane, the Silbervogel, which was supposed to have dropped bombs on New York City; in my novel, British intelligence learns of this and tips off the Americans, and they enlist the aid of Robert H. Goddard, the inventor of the liquid-fuel rocket, to head a crash program to develop a deterrent.

I had a lot of fun researching and writing this book. It was originally a short story, "Goddard's People", which was one of my first published works, and later became a screenplay for a movie that was never produced. This time around, I was able to expand the story considerably, and put a lot of stuff in there that I didn't before. There's a chapter that takes place in Paris, for instance, that I'm particularly proud of ... I went to France to research it, and so visited the Notre Dame and walked the streets of the Left Bank to get the details right. This is the sort of thing that makes writing fun.

Nick: Future plans : What are you working on and what can we expect from Allen Steele in the near future ?

Steele: I'm currently writing a series of novellas -- short novels, really -- for Asimov's Science Fiction that are about a generations-long effort to build and launch the first starship. The timeline stretches from 1939 to the 25th century, and presents a different take on interstellar exploration than the Coyote series. The first story, "The Legion of Tomorrow", will be in the July issue. The second story, "The Prodigal Son", has just been sold and will appear sometime later in the year, and I'm now working on the third story, "The Long Wait".

I'll also have a long essay, "Tomorrow Through The Past", appear sometime this year in Asimov's. It's an assessment of the current state of the science fiction -- "the good, bad, and ugly", to borrow the title of my favorite spaghetti western -- that's expanded from the Guest of Honor speech I delivered at the Philcon science fiction convention late last year. I think some of the things I wrote may be controversial; we'll have to see what the reaction will be. Which is the way it always is, really. I write these things and put them out there, and the response from my readers is always interesting.

Nick: Well we ended up with this Allen ,in greeting you I make you the classic final question of Nocturnia : There is a question to which you would have responded willingly and yet I will not addressed?

Steele: I can't think of anything else, really. Again, thanks for inviting do this interview. Great questions -- glad to answer them!