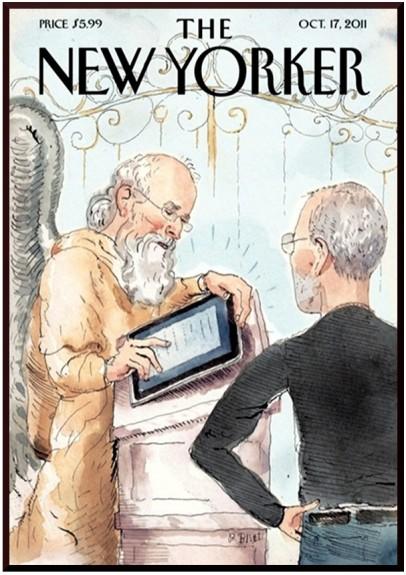

La copertina del New Yorker ha suscitato commenti furiosi ( Jobs era buddista).

Cosa c'entra con le lavatrici? C'entra, c'entra. Verso l'inizio dell'articolo si racconta di come funzionava la scelta di una nuova lavatrice in casa Jobs (e delle esaltanti discussioni conviviali alla tavola dei Jobs):"European washing machines, Jobs discovered, used less detergent and less water than their American counterparts, and were easier on the clothes. But they took twice as long to complete a washing cycle. What should the family do? As Jobs explained, 'We spent some time in our family talking about what’s the trade-off we want to make. We ended up talking a lot about design, but also about the values of our family. Did we care most about getting our wash done in an hour versus an hour and a half? Or did we care most about our clothes feeling really soft and lasting longer? Did we care about using a quarter of the water? We spent about two weeks talking about this every night at the dinner table.'"Il pezzo di Gladwell prosegue, sempre citando dalla biografia, e descrive il famigerato caratteraccio di Jobs:"Jobs, we learn, was a bully. 'He had the uncanny capacity to know exactly what your weak point is, know what will make you feel small, to make you cringe,' a friend of his tells Isaacson. Jobs gets his girlfriend pregnant, and then denies that the child is his. He parks in handicapped spaces. He screams at subordinates. He cries like a small child when he does not get his way. He gets stopped for driving a hundred miles an hour, honks angrily at the officer for taking too long to write up the ticket, and then resumes his journey at a hundred miles an hour. He sits in a restaurant and sends his food back three times. (...) In the hospital at the end of his life, he runs through sixty-seven nurses before he finds three he likes. 'At one point, the pulmonologist tried to put a mask over his face when he was deeply sedated,' Isaacson writes:

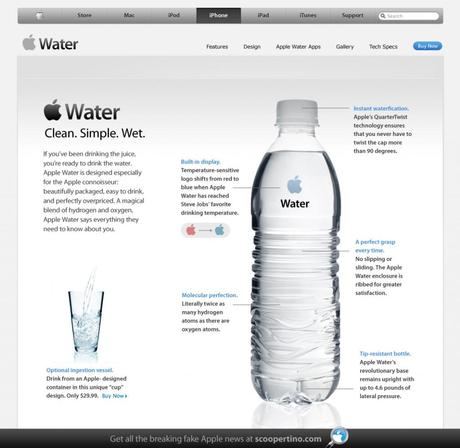

Apple Water (click to enlarge)

'Jobs ripped it off and mumbled that he hated the design and refused to wear it. Though barely able to speak, he ordered them to bring five different options for the mask and he would pick a design he liked. . . . He also hated the oxygen monitor they put on his finger. He told them it was ugly and too complex.'" (...)"The great accomplishment of Jobs’s life is how effectively he put his idiosyncrasies—his petulance, his narcissism, and his rudeness—in the service of perfection."C'è poi un'interessante digressione linguistica, dove si parla della creazione del famoso slogan:"They debated the grammatical issue: If 'different' was supposed to modify the verb 'think,' it should be an adverb, as in 'think differently.' But Jobs insisted that he wanted 'different' to be used as a noun, as in 'think victory' or 'think beauty.' Also, it echoed colloquial use, as in 'think big.' Jobs later explained, 'We discussed whether it was correct before we ran it. It’s grammatical, if you think about what we’re trying to say. It’s not think the same, it’s think different. Think a little different, think a lot different, think different. ‘Think differently’ wouldn’t hit the meaning for me.'"E infine, qualche parola sul rapporto tra Jobs e Bill Gates:"Perhaps this is why Bill Gates—of all Jobs’s contemporaries—gave him fits. Gates resisted the romance of perfectionism. Time and again, Isaacson repeatedly asks Jobs about Gates and Jobs cannot resist the gratuitous dig. 'Bill is basically unimaginative,' Jobs tells Isaacson, 'and has never invented anything, which I think is why he’s more comfortable now in philanthropy than technology. He just shamelessly ripped off other people’s ideas.'After close to six hundred pages, the reader will recognize this as vintage Jobs: equal parts insightful, vicious, and delusional. It’s true that Gates is now more interested in trying to eradicate malaria than in overseeing the next iteration of Word. But this is not evidence of a lack of imagination. Philanthropy on the scale that Gates practices it represents imagination at its grandest. In contrast, Jobs’s vision, brilliant and perfect as it was, was narrow."