It could save your life for real. Do a medical checkup before making a sport activity

Sembra una specie di epidemia. Con la complicità e la velocità delle notizie, in quest’ultimo periodo abbiamo sentito di un numero altissimo di giovani sportivi che sono morti in gara, o in allenamento, oppure sono stati presi per i capelli (come Antonio Cassano).

Tutto il giornalismo – sportivo e non – si è interrogato su diversi problemi: la tempestività dei soccorsi, il possibile coinvolgimento di sostanze dopanti, lo stress agonistico eccessivo causato da troppi match e poco tempo per riposare, la professionalità delle visite medico-sportive. Christian Marchetti ha intervistato qualche giorno fa il presidente della commissione medica FIR, che ha sollevato diverse questioni importanti, sottolineando come nelle competizioni non professionistiche si incontri qualche difficoltà nella gestione logistica ed economica dell’aspetto medico-sanitario, dalla presenza di personale medico durante le partite alla visita di idoneità medico sportiva. In pratica, le società hanno pochi soldi e li devono far bastare.

Quando praticavo atletica negli anni del liceo, c’erano i Giochi della Gioventù. Per parteciparvi, dovevi passare l’esame di idoneità sportiva, anche se appartenevi a una società o un club e risultavi già idoneo per l’attività agonistica.

L’esame prevedeva un test delle urine, un elettrocardiogramma a riposo e uno sotto sforzo, la spirometria e una visita generale (udito, vista etc). Prima della visita dovevi compilare un foglio con diverse domande: gruppo sanguigno, allergie, operazioni chirurgiche e traumi subiti. Ma soprattutto, c’era un intero lato del foglio dedicato alle ereditarietà/familiarità a qualche disturbo, come il diabete o le patologie cardiache.

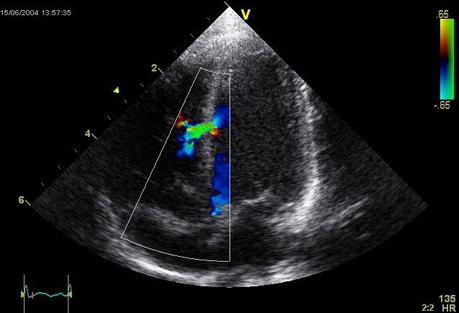

Bastava una minuzia per bloccarti o per spedirti in cardiologia per un ecocardiogramma. Un anno, la nostra discobola è stata bloccata per una banale micosi. A un altro ragazzo è stata scoperta una cardiomiopatia ipertrofica, la stessa che ha fermato campioni olimpici come Domenico Fioravanti.

Sono scomparse – per colpa di tanti fattori che è inutile elencare qui – momenti importantissimi, non solo sociali, ma anche “organici” (passatemi il termine) per la crescita e la formazione di un giovane. Come la visita per i Giochi della Gioventù, o peggio, la visita di leva, dove moltissimi ragazzi scoprivano cose che gli avrebbero potuto salvare la vita. D’altronde, era inutile e poco economico cancellare la leva obbligatoria ma comunque tenere in piedi la visita di leva.

Infine, aggiungo quattro spunti di riflessione.

1- Le morti improvvise sono per lo più causate da patologie “latenti” o nascoste, per lo più di natura cardiaca. Quello che la gente chiama “destino” o “fatalità” inferisce in una percentuale tristemente molto bassa, a mio modo di vedere le cose. Sostituire nell’opinione pubblica il concetto di “fato” con quello di “prevenzione” sarebbe già un passo enorme in avanti.

2- Il fatto che l’Italia sia all’avanguardia e più attenta nelle procedure di idoneità sportiva degli atleti non significa che le federazioni e le società si debbano cullare sugli allori. Ho detto un’ovvietà? L’ho detta.

3- La lotta al doping è forte, ma non basta. C’è chi si accascia tragicamente sul campo a vent’anni, ma c’è anche chi si spegne lentamente a 40, 50 anni. Vogliamo continuare a chiamarlo “fato”? Ci sono più Florence Griffith-Joyner in giro di quello che pensate.

4- Se un tesserato ha un problema che lo mette in pericolo di vita, anche se il rischio è molto minimo o risibile, la società lo deve “licenziare”. Oppure deve pagare il dazio di averlo tesserato senza accertarsi delle sue reali condizioni fisiche. Lo so bene che qui si entra nel delicato tema del diritto del lavoro, ma non pensate che la vita sia più importante, comunque?

–

It sounds like a pandemic. We have recently attended to a several young sportsmen deaths, thanks to the complicity and the speed of the news. These athletes died during a match or a training, while the lucky one (as Antonio Cassano, for example) have been brought back from the brink.

The whole journalism world is wondering about some issues: the timeliness of the rescue, the possible involvement of doping substances, the huge stress caused by too much games with few time to rest, the professionalism of sport-medical checkups. Christian Marchetti interviewed for his “SoloRugby” website the chairmen of the Italian Rugby Union Federation’s medical commission, who raised several important objections. Besides, he pointed out that there are quite a few troubles during non-professional competitions, especially when they have to manage logistic and economical aspects of the medical field, from the presence of medical staff during the matches to the checkups certifying sport ability. In few words, sport clubs have no so much money and they have to make them enough for everything.

When I practiced athletics during the high school time there were school competitions called “Giochi della Gioventù” (Youth Games). If you wanted to take part in them, you had to pass the sport ability test, even if you already had it as a sport club athlete. The examination entailed the following tests: urine, eye, hearing test, electrocardiogram (at rest and under stress) and spirometry. Before the checkup you might fill out a sheet with some questions: blood type, allergies, surgeries, traumas. And most of all an entire side of the sheet was dedicated to the genetic/family history to some decease as diabetes or cardiac pathologies.

Just a trifle was enough to stop your activity or bring you to the cardiology ward for an echocardiogram. Once our discus thrower was stopped due to a simple mycosis. Another boy was stopped because they discovered an hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the same one that has stopped Olympic champions such as Domenico Fioravanti.

Because of many factors – that it is pointless to list here – important social and “biologic” (let me pass the word) moments are disappeared forever. A huge loss for the growth and the education of a young man. Just like the checkup for the Youth Games, or worse the army medical, where many young men discovered things that could save their lives. Moreover it was unnecessary and uneconomical canceling compulsory military service holding up army medical.

Finally, let me add four points as a breathing space.

1- Sudden deaths are mostly caused by “latent” or hidden diseases, in most case cardiac. What people use to call “fate” or “inevitable” sadly infers a very low percentage, in my opinion. Changing the concept of “fate” in “prevention” among the public opinion would be a huge step forward.

2- The fact that Italy is on the cutting edge and more careful in the sport medicine field does not mean that federations and clubs should be rest on their laurels. Did I said the obvious? Yes, I did.

3- The fight against doping is strong, but it is not enough. There are those who tragically collapse on the ground at 20 years, but there are also those who slowly pass away at 40, 50 years. Do we want to continue to call it “fate”? There are more Florence Griffith-Joyner around than you think.

4- If a fully paid-up athlete has any kind of problem, the club must “fire” him/her. Or must pay the duty of having hired him/her without making sure of the current physical condition. I well know that this means entering the sensitive issue of labor law, but don’t you think that life is more important, anyway?