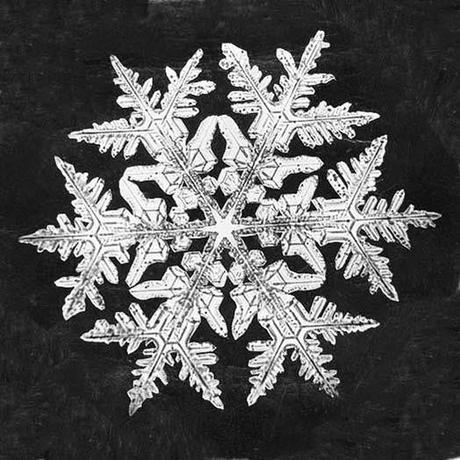

“Every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no one design was ever repeated. When a snowflake melted, that design was forever lost. Just that much beauty was gone, without leaving any record behind.“

- Wilson Bentley

"Ogni cristallo era l'espressione di un capolavoro e nessun disegno mai si ripeteva. Quando un fiocco di neve si scioglieva, quel disegno andava perduto per sempre. Così tanta bellezza se ne andava senza lasciare alcuna traccia di sé. "

- Wilson Bentley

Wilson Alwyn Bentley venne alla luce il 7 febbraio 1865, a Gerico, Vermont, dove crebbe nella fattoria di famiglia, e dove ogni anno la neve rimaneva a ricoprire ogni cosa per tutto l'inverno con uno spessore di circa 120 centimetri. Fin da bambino era affascinato dalla natura che il luogo in cui viveva gli offriva e non amava l'inverno che recava con sé quella fitta coltre di neve che lo costringeva a stare rinchiuso in casa privandosi della frequenza a scuola (fortunatamente la madre che era insegnante elementare provvide alla sua educazione ed istruzione) e dei giochi all'aria aperta.

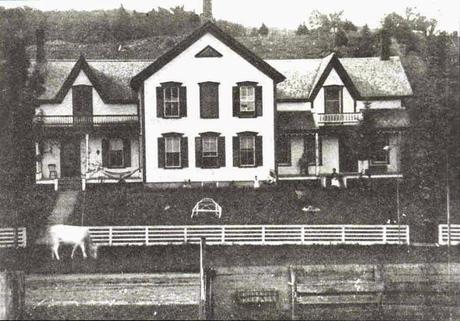

La fattoria della famiglia Wilson a Gerico

Da adolescente crebbe il suo interesse per i fiocchi di neve, imprescindibili compagni della stagione fredda, e quando, a quindici anni, sua madre gli fece dono di un vecchio microscopio, cominciò con il realizzare parte del suo sogno, osservando la forma affascinante, l'esclusività e l'irripetibilità di ciascuno di essi:"Quando gli altri ragazzi della mia età giocavano con popguns e fionde, io ero assorto nello studio le cose sotto questo microscopio: gocce d'acqua, piccoli frammenti di pietra o di una piuma dell'ala di un uccello. Ma sempre, fin dall'inizio, sono stati i fiocchi di neve che mi hanno affascinato di più... Sotto il microscopio ho scoperto che i fiocchi di neve erano miracoli di bellezza, e sembrava un peccato che questa bellezza non potesse essere vista ed apprezzata da altri. Sono quindi stato preso con passione dalla voglia di dimostrare alla gente qualcosa di questa meravigliosa bellezza, dall'ambizione di diventare, in qualche misura, il suo conservatore. " 1;

a tal fine egli li collocò su di una superficie di velluto nero al fine di vederli il più chiaramente possibile e cercò di riprodurli in disegni, ma la loro complessità e la velocità con cui si discioglievano e perdevano la loro forma originaria fece fallire questo suo primo proposito.

"Quando avevo non più di diciassette anni, mia madre convinse mio padre a comprarmi una macchina fotografica da collegare al microscopio nell'apparecchiatura che sto tutt'ora usando. Costò, già allora, un centinaio di dollari! Potete immaginare, o forse no, a meno che non sappiate cosa significhi essere un agricoltore, quanto mio padre odiasse spendere tutti quei soldi per quello che a lui sembrava null'altro che un futile capriccio da ragazzo.

In qualche modo mia madre lo persuase, ma mai si convinse che ne valse la pena. Sia lui che mio fratello maggiore hanno sempre pensato che stavo ingannando il tempo armeggiando con i fiocchi di neve". 2

Quando Wilson ebbe la macchina fotografica a mantice ed il microscopio è presumibile pensare che abbia trascorso molte settimane provando diversi modi per collegarli insieme e per mettere a fuoco rapidamente sullo schermo di vetro smerigliato posto sul retro della telecamera quello che vedeva il microscopio; aveva sì in mente di collegarli, ma innanzitutto dovette pensare ad un sostegno che li reggesse entrambi ed uniti, perciò, prima di procedere con la sperimentazione si procurò un tavolo in legno alto circa tre piedi, un po' più di due piedi di lunghezza, e largo poco più di un piede.

La struttura in legno, piuttosto fittile e tenuta insieme solo da chiodi, fa pensare che sia stata realizzata molto fugacemente al fine di consentirgli di andare avanti con l'esperimento. Ciò suggerisce che egli si sia procurato il tavolo altrove e fece da sé il telaio che, seppur grezzo e per niente elegante, servì mirabilmente ai suoi propositi per oltre cinquanta anni.

La macchina fotografica aveva un ingombro tale che per fare spazio al microscopio doveva sporgere di circa un piede al di fuori del tavolo; egli rimosse sia l'oculare del microscopio che l'obiettivo della telecamera, poi spinse il microscopio verso la fotocamera finché il tubo o corpo principale stesso rientravano in un manicotto a tenuta di luce attaccato alla parte anteriore della macchina. Utilizzando poi la manopola di messa a fuoco cercò di ottenere un'immagine ingrandita al massimo sullo schermo di vetro smerigliato della fotocamera di tutto ciò che era posto sul piano del microscopio. Ma come si fa a ottenere un cristallo di neve sul vetrino di fronte al microscopio? Bentley aveva già trovato la soluzione a tale problema durante i lunghi mesi invernali degli anni precedenti quando cercò di disegnare i cristalli che vedeva sotto il microscopio.

Raccoglieva i cristalli su di una piccola lavagna ed in piedi, al di fuori della legnaia, guardava i fiocchi di neve ed cristalli che vi cadevano sopra, osservandoli occasionalmente, con una lente di ingrandimento. Se non vedeva ciò che intendeva fotografare, spazzolava via la neve con una piuma di tacchino e ricominciava da capo, ma quando trovava un cristallo che voleva fotografare, si precipitava all'interno della legnaia per trasferirlo su di un vetrino del microscopio.

Raccoglieva i cristalli su di una piccola lavagna ed in piedi, al di fuori della legnaia, guardava i fiocchi di neve ed cristalli che vi cadevano sopra, osservandoli occasionalmente, con una lente di ingrandimento. Se non vedeva ciò che intendeva fotografare, spazzolava via la neve con una piuma di tacchino e ricominciava da capo, ma quando trovava un cristallo che voleva fotografare, si precipitava all'interno della legnaia per trasferirlo su di un vetrino del microscopio.Ed è qui che inizia la parte più delicata di tutto il processo: utilizzando una setola di una delle scope di saggina della madre, egli toccava delicatamente la parte centrale del cristallo di neve, lo prendeva e lo collocava nel centro del vetrino del microscopio, operazione per cui era necessaria una mano ferma tenuto conto del fatto che cristalli erano solo un sedicesimo di pollice di diametro. A tale proposito negli anni successivi, Bentley disse: " La mia mano è perfettamente ferma... non ho mai usato liquori, tabacco, o altri stimolanti che colpiscono i nervi. "3

In questa parte così delicata del procedimento, Bentley conduceva una vera e propria lotta contro il tempo: rapidamente metteva il vetrino sotto il microscopio di osservazione per assicurarsi che il cristallo di neve si fosse conservato intatto;

metteva poi la diapositiva sul piano del microscopio e si affrettava a raggiungere la parte posteriore della fotocamera, otteneva rapidamente una messa a fuoco sul vetro smerigliato, lo rimuoveva e lo sostituiva con una lastra fotografica, esponendo alla luce l'immagine ingrandita del cristallo di neve per circa 30 secondi. Se non poteva stare all'aperto mutuava la luce semplicemente puntando la telecamera verso una finestra della legnaia per consentirle di passare attraverso il cristallo di neve nel suo 'percorso' verso la lastra fotografica. Utilizzando questa tecnica di luce trasmessa, Bentley doveva aspettare il tempo necessario perché la luce penetrasse a mostrare non solo la superficie ma la struttura interna del cristallo di neve. Poiché egli aveva rimosso l'otturatore dalla fotocamera ne costruì uno da sé con una piccola scheda nera montata davanti all'obiettivo: toglieva la carta quando il tempo di esposizione necessario era finito ed ogni volta la sostituiva; la piastra era quindi pronta per lo sviluppo. Era nata così quella che ancora oggi si chiama FOTOMICROGRAFIA, di cui egli fu l'involontario inventore e pioniere. Dopo molte sperimentazioni, egli riuscì a fotografare il suo primo fiocco di neve il 15 GENNAIO 1885 e da allora cominciò il suo vero grande lavoro, quello di coniugare straordinariamente scienza, natura ed arte e guadagnando il soprannome di Snowflake Man, L'uomo fiocco di neve.

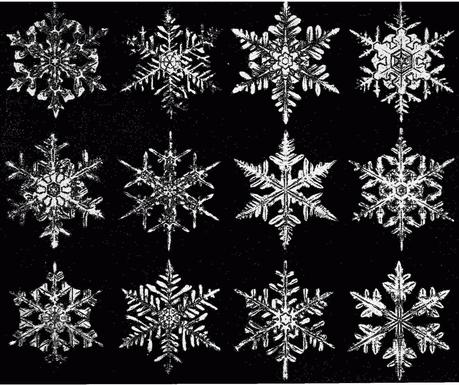

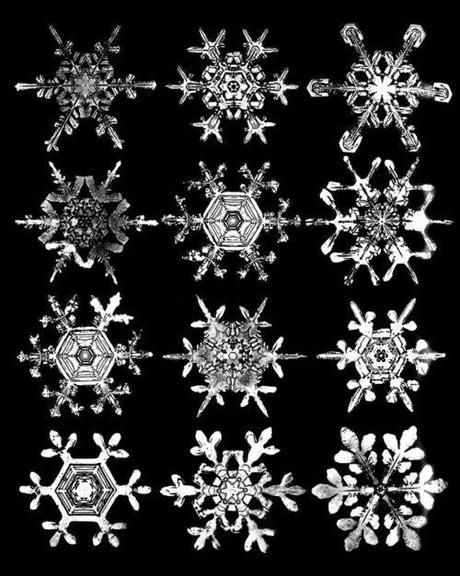

metteva poi la diapositiva sul piano del microscopio e si affrettava a raggiungere la parte posteriore della fotocamera, otteneva rapidamente una messa a fuoco sul vetro smerigliato, lo rimuoveva e lo sostituiva con una lastra fotografica, esponendo alla luce l'immagine ingrandita del cristallo di neve per circa 30 secondi. Se non poteva stare all'aperto mutuava la luce semplicemente puntando la telecamera verso una finestra della legnaia per consentirle di passare attraverso il cristallo di neve nel suo 'percorso' verso la lastra fotografica. Utilizzando questa tecnica di luce trasmessa, Bentley doveva aspettare il tempo necessario perché la luce penetrasse a mostrare non solo la superficie ma la struttura interna del cristallo di neve. Poiché egli aveva rimosso l'otturatore dalla fotocamera ne costruì uno da sé con una piccola scheda nera montata davanti all'obiettivo: toglieva la carta quando il tempo di esposizione necessario era finito ed ogni volta la sostituiva; la piastra era quindi pronta per lo sviluppo. Era nata così quella che ancora oggi si chiama FOTOMICROGRAFIA, di cui egli fu l'involontario inventore e pioniere. Dopo molte sperimentazioni, egli riuscì a fotografare il suo primo fiocco di neve il 15 GENNAIO 1885 e da allora cominciò il suo vero grande lavoro, quello di coniugare straordinariamente scienza, natura ed arte e guadagnando il soprannome di Snowflake Man, L'uomo fiocco di neve.Bentley dedicò la sua esistenza, trascorsa interamente presso la fattoria di famiglia a Gerico, a dimostrare che ogni fiocco di neve è qualcosa di unico: descrivendoli poeticamente come "fiori di ghiaccio" o "piccoli miracoli di bellezza" riuscì ad immortalare oltre 5.000 di queste effimere opere d'arte nel corso della sua vita, dimostrando inoltre che custodiscono piccole differenze se osservate da un lato piuttosto che dall'altro, suscitando grande interesse al punto che il frutto del suo operato venne richiesto dal Museo Mineralogico di Harvard e dall'Università del Vermont.

Oggi le sue fotografie sono custodite presso le istituzioni accademiche di tutto il mondo ed è lo Smithsonian Institute (a cui egli inviò 500 stampe nel 1903 per esser certo che fossero conservate con amore e cura per i posteri) a detenerne tutt'ora il record globale nei propri archivi.

La sua ossessione per l'acqua nelle sue varie forme e manifestazioni lo condusse inoltre a misurare le gocce di pioggia e a fotografarne le forme nel gelo e nella rugiada.

Quasi ironicamente, ma molto tristemente, la neve che gli aveva dato il successo lo strapperà alla vita essendosi egli spento dopo aver contratto la polmonite conseguentemente ad aver vagato per sei miglia sotto una bufera cercando la strada per tornare a casa.

Viene così realmente da pensare alle parole di Elsa Morante:

Si direbbe, in realtà, all'epilogo di certi destini, che noi stessi, per una nostra legge organica, fin dall'inizio, insieme con la vita, abbiamo scelto anche il modo della nostra morte.

Elsa Morante, Aracoeli, 1982

A presto miei cari ♥

Fonti bibliografiche:

Duncan C. Blanchard, The Snowflake Man: A Biography of Wilson A. Bentley, Mcdonald & Woodward Pub Co, 1998

Duncan C. Blanchard, Bentley’s Struggle to Photograph Snow Crystals, Snowflake Bentley - The Official Web Site of Wison A.Bentley (1865 - 1931)

Snowflake Bentley - The Official Web Site of Wison A.Bentley (1865 - 1931)

- http://snowflakebentley.com/

Citazioni:

1 - 2 - 3: Duncan C. Blanchard, Bentley’s Struggle to Photograph Snow Crystals, Snowflake Bentley - The Official Web Site of Wison A.Bentley (1865 - 1931)

“Every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no one design was ever repeated. When a snowflake melted, that design was forever lost. Just that much beauty was gone, without leaving any record behind.“

- Wilson Bentley

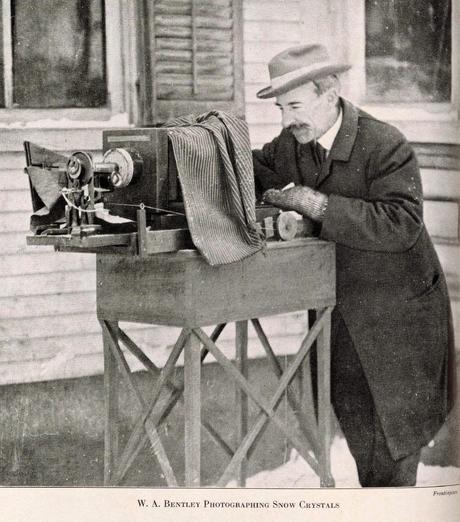

- picture 1

Wilson Alwyn Bentley enter the world on February 7th, 1865, in Jericho, Vermont, where he grew up in the family farm, and where every year the snow remained to cover everything through the whole winter with a thickness of about 120 cm. Even as a child he was fascinated by the nature of the place he lived in and didn't like Winter bringing with it that thick blanket of snow that forced him to stay locked up inside his home house depriving him of school attendance (fortunately his mother who was a teacher provided for his education) and outdoor games.

- picture 2 - The Wilsons' farm in Jerico

As a teenager, his interest for snowflakes, indispensable companions of the cold season, grew more and more,and when, at the age of fifteen, his mother gifted him an old microscope, he began to realize part of his dream, observing the charming, the exclusivity and uniqueness of the shape of each of them;

“When the other boys of my age were playing with popguns and slingshots, I was absorbed in studying things under this microscope: drops of water, tiny fragments of stone a feather from a bird’s wing. But always, from the very beginning, it was the snowflakes that fascinated me most. . . . Under the microscope I found that snowflakes were miracles of beauty, and it seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others. I became possessed with a great desire to show people something of this wonderful loveliness, an ambition to become, in some measure, its preserver.”;he thought to place them on a surface of black velvet in order to see them as clearly as possible and tried to play them in designs, but their complexity and the speedness with which they melted and lost their original form did fail this first attempt of his.

“When I was seventeen years old, my mother persuaded my father to buy for me the camera and microscope which I developed into the apparatus I am still using. It cost, even then, one hundred dollars! You can imagine, or perhaps you cannot, unless you know what the average farmer is like, how my father hated to spend all that money on what seemed to him a boy’s ridiculous whim.

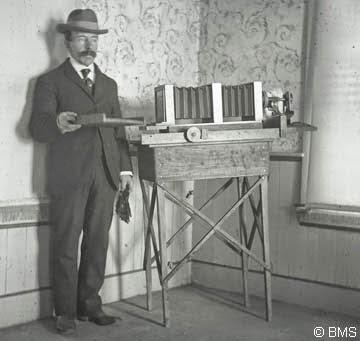

- picture 3

“Somehow my mother got him to spend the money, but he never came to believe it had been worthwhile. He and my elder brother always thought I was fooling away my time, fussing with snowflakes.”

When Wilson took the bellows camera and the microscope is estimated to think that he spent many weeks trying different ways to connect them together and to focus quickly on the screen he saw on the back of the camera the frosted glass he saw in his microscope; yes he had in mind to connect them, but first he had to think of a support that would put them together and, therefore, before proceeding with the experimentation he procured a wooden table about three feet tall, a bit more than two feet in length, and large a little more than a foot.

- picture 4

The wooden structure, rather clay and held together only by nails, suggests that it was made very briefly to allow him to go ahead with his experiment. This suggests that he got the table elsewhere and made himself the structure which, although crude and not elegant at all, admirably served his purposes for over fifty years.

The camera had such a big footprint that to make space to the microscope it should protrude about one foot outside of the table; he removed both the eyepiece of the microscope than the objective of the camera, then pushed the microscope to the camera until the pipe or main body, covered in a light-tight sleeve, was attached to the front of the machine. Then using the knob Focus he tried to get a maximized image on the frosted glass of the camera of all that was placed on the plane of the microscope. But how do you get a snow crystal on the glass in front of the microscope? Bentley had already found the solution to this problem during the long winter months of the previous years when he tried to draw the crystals seen under the microscope.

- picture 5 on the left - He collected the crystals on a small blackboard and, standing outside the woodshed, watching the snowflakes and crystals that fell over it, he observed them occasionally with a magnifying glass. If he didn't see what he intended to photograph, he brushed away the snow with a feather of turkey and started again, but when he found a crystal that wanted to photograph, he rushed inside the woodshed to transfer it to a microscope slide.And it's here that begins the most delicate part of the whole process: using a bristle of one of the sorghum brooms of his mother, he gently touched the central part of the snow crystal, took him and placed him in the center of the microscope slide, operation for which was needed a very steady hand if we think that some crystals were only one-sixteenth of an inch in diameter. In this regard, a few years later, Bentley said:

“My hand is perfectly steady... have never used liquor, tobacco, or any other stimulants that affect the nerves.” 3

In this so delicate part of the procedure, Bentley led a real race against time: he quickly put the slide under the microscope to observe and to make sure that the crystal of snow had preserved intact; then put the slide on the plane of the microscope, and hastened to reach the back of the camera, to obtain

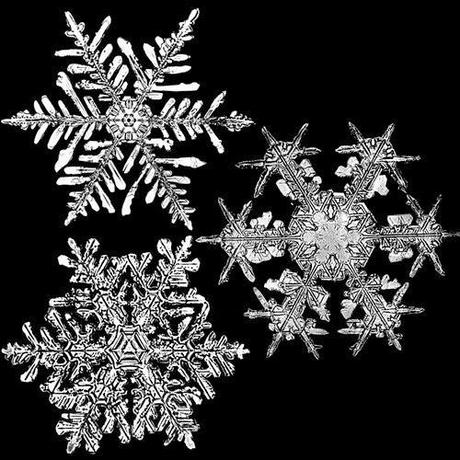

- picture 6 on the right - quickly focused on the ground glass, removed it and replaced it with a photographic plate, exposing to the light the enlarged image of the snow crystal for about 30 seconds. If he couldn't stay outdoors he got the light simply by pointing the camera at a window of the woodshed for it to go through the snow crystal in its 'way' to the photographic plate. Using this technique of transmitted light, Bentley had to wait for the time required for the light to penetrate the snowflake as to show not only its surface but its internal structure. Since he had removed the bolt from the camera he built one for himself with a small black board mounted in front of the lens: he took off the paper when the exposure time was over, and each time he substituted it; the slide was then ready for the development. So it was born so what today we still call PHOTOMICROGRAPHY, of which he was the involuntary inventor and pioneer. After many trials, he was able to photograph his first snowflake on January the 15th, 1885 and since then began his real great job, that of combining extraordinarily science, nature and art and together earning the nickname of Snowflake Man.

- video

Bentley devoted his existence, spent entirely at the family farm in Jericho, to show that every snowflake is unique: poetically describing them as "ice flowers" or "little miracles of beauty" was able to capture more than 5,000 of these ephemeral works of art in the course of his life, by demonstrating that they hold small differences when viewed from one side or on the other, arousing great interest to the point that the result of his work was appreciated and prompted by the Mineralogical Museum at Harvard and the Vermont University.

- picture 7

- picture 8

- picture 9

- picture 10

- picture 11

- picture 12

- picture 13

Today, his photographs are kept in academic institutions around the world and it is the Smithsonian Institute (to which he sent 500 prints in 1903 to be sure that they were preserved with love and care for posterity) that still owns the global record in its archives.His obsession for water in its various forms and manifestations led him also to measure the raindrops and to photograph their shapes in the frost and dew.Almost ironically, but very sadly, the snow that had given him his success, will steal his life having he expired after contracting pneumonia consequently to have wandered for six miles in a blizzard looking his way back home.It recalls to my mind Elsa Morante's words:

It would seem, in fact, by the epilogue of certain destinies, that we ourselves, for our organic law, from the beginning, along with our own life, we have also chosen the way of our death.

Elsa Morante, Aracoeli, 1982

See you soon my loved ones ♥

Bibliographic sources:

Duncan C. Blanchard, The Snowflake Man: A Biography of Wilson A. Bentley, Mcdonald & Woodward Pub Co, 1998

Duncan C. Blanchard, Bentley’s Struggle to Photograph Snow Crystals, Snowflake Bentley - The Official Web Site of Wison A.Bentley (1865 - 1931)

Snowflake Bentley - The Official Web Site of Wison A.Bentley (1865 - 1931) - http://snowflakebentley.com/

Quotations:

1 - 2 - 3: Duncan C. Blanchard, Bentley’s Struggle to Photograph Snow Crystals, Snowflake Bentley - The Official Web Site of Wison A.Bentley (1865 - 1931)