(C) Editions Orphée – www.editionsorphee.com

Fino al 1920 circa, la musica originale per chitarra è stata creata quasi esclusivamente da chitarristi-compositori. Rari sono i casi di personalità che hanno saputo equilibrare nella loro opera i valori musicali e la ricerca idiomatica, e nemmeno Fernando Sor e di Mauro Giuliani, indubbiamente i maestri di maggior spicco nella prima metà dell’Ottocento, sono immuni da critiche. Dal momento in cui Manuel de Falla compose il suo Homenaje (1920) e in cui Segovia incominciò la sua opera di persuasione presso i compositori, la storia della musica per chitarra registra un fatto nuovo, di importanza fondamentale: nasce un nuovo repertorio basato sì sulla valorizzazione dello strumento e del suo idioma, ma anche, e soprattutto, su una ricerca musicale purificata da ogni progetto dimostrativo. Da allora in poi, il repertorio della chitarra si è innalzato nella qualità e si è espanso prodigiosamente, giovandosi dell’apporto di compositori di tutte le tendenze, da quelle conservatrici a quelle d’avanguardia.

A partire dagli anni Sessanta, ha incominciato a prendere forma, nella storia della musica per chitarra, una terza fase: nuovi chitarristi-compositori, ben consci dei valori del repertorio formatosi nei quattro decenni precedenti, hanno dato avvio a una ricerca in cui la forma musicale—lato debole di molta musica per chitarra scritta da virtuosi—si è consolidata e, insieme, si è giovata di nuove, e talvolta geniali, invenzioni idiomatiche. Il nuovo repertorio creato da alcuni chitarristi-compositori si è così disposto parallelamente alle composizioni di illustri musicisti che hanno seriamente investigato il campo della composizione chitarristica: accanto alle musiche di autori come Henze, Britten, Petrassi, Maderna, Ohana, Donatoni, Ferneyhough, Berio e tanti altri (quasi tutti i maggiori musicisti della nostra epoca) esistono le musiche di autori come Leo Brouwer, Gilbert Biberian, Dusan Bogdanovic, etc., che sviluppano ricerche di valori musicali autonomi e autentici, in simbiosi con un inesauribile progresso della “lingua” chitarristica.

In questa linea di ricerca avanzata e specifica, che mira a dar vita a una musica per chitarra in cui suono e forma musicale coesistono fin dalla concezione originaria e si sviluppano necessariamente insieme, operano alcuni giovani autori. La loro opera si diversifica nettamente da quella dei molti chitarristi-compositori che scrivono composizioni per l’intrattenimento facile, a fini commerciali, anzi, è evidente in loro il deliberato proposito di proseguire il cammino di una nuova filosofia chitarristica che inevitabilmente seleziona senza remissione i suoi adepti, siano essi interpreti o ascoltatori.

Mark Delpriora è una delle figure più rappresentative di questa nuova tendenza. Docente di storia della musica per chitarra alla Manhattan School of Music, ha assimilato fin dagli anni giovanili tutto lo scibile chitarristico alla luce di una cultura in cui non è mai stato tracciato il confine tra il sapere dello storico e del musicologo e il fare del musicista attivo. Come concertista, egli professa—si direbbe naturalmente—le due Sonate del ciclo Royal Winter Music di Hans Werner Henze come una carta di credito che non abbisogna di ulteriori aggiunte. Era altrettanto naturale che la sua ricerca di chitarrista-compositore sfociasse in un’opera di possente drammaturgia chitarristica, qual è la presente “Third Sonata”. Più che sottolinearne l’ampiezza, sembra opportuno mettere in rilievo la complessa stratificazione culturale che la sottende. E’ fuori di dubbio l’eredità della musica tardoromantica per pianoforte, che Delpriora ha meditato, partendo da Brahms, Liszt, Franck, Fauré, fino alle estreme propaggini est-americane, che si spiegano fascinosamente in quella Sonata di Samuel Barber che Horowitz rivelò negli anni Cinquanta. L’eloquio sonatistico di Delpriora è quindi il frutto di una approfondita riflessione sull’eco romantico-pianistica sopravvissuta flebilmente alle categoriche negazioni dell’avanguardia post-weberniana, di cui l’autore non è comunque ignaro. Vi è inoltre, e ancora più specificamente, in quest’opera di Delpriora, una sottile e delicata trama autobiografica o addirittura ancestrale: la coscienza di una remota origine familiare lo induce a creare una musica il cui correlativo immaginifico è un paesaggio italiano, anzi veneto, e a rapportarsi con una temperie culturale e musicale in cui—nella vaghezza fantasmatica del sogno—trascorrono, come in una processione, lacerti musicali italici, da Monteverdi a Ghedini, da Corelli a Petrassi, suggestioni letterarie—da Petrarca a Foscolo (il cui Sonetto Alla sera dev’essere stato all’origine del secondo movimento, una sorta di Abendlied italianeggiante) pittoriche e forse anche teatrali.

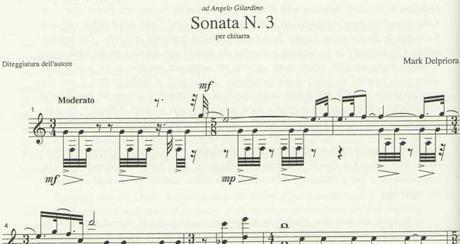

Un insieme così complesso di elementi originari non avrebbe potuto manifestarsi in una forma coerente se non attraverso una riflessione molto elaborata: lo stesso titolo di “Sonata”, rispetto alla forma—o alle forme—musicali adunate e fuse nei sei movimenti, è frutto di un’elaborazione, e richiede un’interpretazione: se l’elaborazione tematica del primo tempo (“Moderato”) è intelligibile nel senso propriamente classico del titolo “Sonata”, e se nulla si oppone al considerare la conclusiva “Passacaglia” come una di quelle serie di Variazioni di cui talvolta consta la Sonata classica, i quattro movimenti centrali richiedono invece di essere visti in un ambito formale in cui la “Sonata” e la “Suite” non sono ben distinte. Conseguenza diretta dell’elaborazione sviluppata da Delpriora è la raffinata proprietà della notazione chitarristica, che in questo lavoro si articola con esemplare flessibilità, facendo coincidere in ogni momento l’architettura del pensiero musicale e quella del segno.

La natura irreale, cioè anti-descrittiva, del sogno italiano di Delpriora, è anche il segreto della particolare, intima vocazione chitarristica della sua “Third Sonata”, un brano che può esistere solo perché esiste la chitarra.

Concludo questa nota introduttiva, che convintamente introduce un’opera per chitarra di forte concezione e di straordinario rilievo, ringraziando Mark Delpriora per l’onore che mi ha reso con la dedica. E’ implicito il riconoscimento al dedicatario di essere uno dei musicisti che più appassionatamente hanno creduto e seguitano e credere nella chitarra come a uno strumento capace di esprimere quello che Carlos Castaneda ha impareggiabilmente definito “Il fuoco dal profondo”, unione di energia creativa e di sopravvivente, inesausta spiritualità.

Angelo Gilardino

Vercelli, Aprile 1998.

(C) 1998 Edizioni Musicali Bèrben

EnglishText

EnglishText

Until around 1920, original music for guitar was composed almost exclusively by guitarists. Among these, few were able to maintain a balance between musical values and an idiomatic command of the instrument; not even Fernando Sor and Mauro Giuliani—without doubt the most significant guitarist-composers of the first half of the nineteenth century—are immune to such criticism. From the moment, however, when Manuel de Falla composed his Homenaje (1920), and when Segovia first undertook his mission among composers on behalf of the guitar, the history of guitar music witnessed an unprecedented development of fundamental importance: a new repertoire was born which, while securely based on an appreciation of the instrument and its idiom, was just as strongly rooted in musical exploration purified of any demonstrative plan. From then on, the repertoire of the guitar has risen in quality, and has expanded prodigiously, enriched by composers of every stylistic tendency from the most conservative to the avant-garde.

Beginning with the 1960s, a third phase of the history of guitar music began to take form: new guitarist-composers, well aware of the values of the repertoire developed over the four preceding decades, have launched an approach to composition in which the musical form—the weakest aspect of much guitar music written by virtuosi—has been consolidated, profiting at the same time from new, and at times brilliant, idiomatic innovations. This new repertoire stands parallel to the compositions of illustrious musicians who have seriously investigated the field of composition for the instrument: alongside pieces by composers such as Henze, Britten, Petrassi, Maderna, Ohana, Donatoni, Ferneyhough, Berio and many others (nearly all of the major composers of our epoch) stand works by composers such as Leo Brouwer, Gilbert Biberian, Dusan Bogdanovic, etc., who are working towards the realization of autonomous and authentic musical values in symbiosis with an inexorable progress of the “language” of the guitar.

Several young composers are working in this vein of advanced and specific research, which aims to give life to guitar music in which sound and musical form coexist from the original moment of conception and are necessarily developed together. Their works are absolutely different from those of the many guitarist-composers concerned primarily with facility of execution, often with commercial ends. On the contrary, what is most evident in these young composers is the determination to pursue the path of a new philosophy of the guitar which inevitably, and without apology, chooses its adepts selectively, be they interpreters or listeners.

Mark Delpriora is one of the most representative figures of this new tendency. Instructor of guitar music at the Manhattan School of Music, he has assimilated since his earliest years all that can be known about the guitar in the light of a culture in which recognizes no boundary between the knowledge of the historian or musicologist and the practical experience of the active musician. As a concert artist, he presents—one would say naturally—the two Sonatas of the cycleRoyal Winter Music of Hans Werner Henze as a kind of credit card in need of no further guarantors. It is just as natural that his research as a guitarist-composer would lead to the work of such powerful dramaturgy for the guitar that is the present “Third Sonata”. Rather than emphasize the dimensions of the work, it seems more appropriate to place in relief the complex cultural stratification which underlies it. This is beyond doubt the heritage of late Romantic piano music, which Delpriora has studied, beginning with Brahms, Liszt, Franck, Busoni, and Faure, and continuing through the more recent offshoots of the northeastern United States, which unfold with such fascination in the Sonata of Samuel Barber that Horowitz performed in the 1950s. The language employed by Delpriora in the Sonata is therefore the fruit of deep reflection on the echoes of the Romantic piano literature which barely survived the categorical rejections of the post-Webern avant-garde (of which the composer is not unaware). In this work of Delpriora there is also, still more specifically, a subtle and delicate autobiographical, even ancestral, content: the knowledge of distant family origins leads him to create a work whose correlative producer of images is the countryside of Italy, or rather of the Veneto region. Here he enters into a relation with a cultural and musical climate in which, in the phantasmal vagueness of a dream, one sees go by, as in a procession, italic musical fragments from Monteverdi to Ghedini, from Corelli to Petrassi, literary allusions from Petrarch to Foscolo (whose sonnet, Alla sera, must have been the source of the second movement, a sort of Italianized Abendlied), as well as pictorial, and perhaps also theatrical, suggestions.

It would not have been possible for so complex a combination of original elements to be made manifest in a coherent musical form if it were not accomplished by means of a very carefully worked-out reflection: the very title of Sonata, with respect to the musical form, or to the forms, is the result of an an elaboration, and requires an interpretation: if the thematic elaboration of the first movement (“Moderato”) is intelligible in the properly classical sense of the term Sonata, and if nothing prevents us from considering the concluding Passacaglia as one of those series of Variations which at times formed part of the classical Sonata, the four central movements demand instead to be understood as occupying a formal region in which the Sonata and Suite are not distinct from one another. A direct consequence of the elaboration developed by Delpriora is the refined propriety of the guitar notation, which is articulated in this composition with exemplary flexibility, uniting at every moment the architecture of the musical thought and that of the sign.

The unreal, that is, anti-descriptive, nature of the Italian dream of Delpriora is also the secret of the particular, intimate approach to the guitar seen in the “Third Sonata”, a piece that can exist only because the guitar exists.

I would like to conclude this introductory note, in which with full conviction I introduce a guitar composition of strong conception and extraordinary distinction, by thanking Mark Delpriora for the honor of seeing it dedicated to me. Implied in this dedication is that I am among those musicians that have most passionately believed, and that continue to believe, in the guitar as an instrument capable of expressing that which Carlos Castaneda has incomparably defined “The Fire From Within”, the union of creative energy and of surviving, inexhaustible spirituality.

[Translation by Alessandra Visconti]

Compra lo spartito | Buy the score

Compra lo spartito | Buy the score

Questo spartito è venduto nei seguenti eShop | This Score is available on these eShops:- Edizioni Musicali Bèrben | berben.it

Mark Delpriora sona il primo movimento della sua Sonata No.3