Nato in Ungheria in una famiglia borghese, Miklós Rózsa studia musica fin dai primissimi anni della sua vita, studia a Lipsia e si perfeziona con Béla Bartók. La sua opera è legata a doppio filo alla produzione di colonne sonore hollywoodiane (ha vinto tre premi Oscar) e la produzione da camera e sinfonica copre sessant’anni.

Quando Angelo Gilardino, nel 1972, scrisse al compositore chiedendogli un brano per chitarra, la risposta fu purtroppo

“[…] mi piacerebbe tanto accogliere la sua proposta, ma proprio non me la sento di scrivere musica per uno strumento del quale ignoro la tecnica e che non ho tempo di studiare[…]”

Era ancora vivo il divieto posto da Hector Berlioz. Quindici anni dopo, anche il chitarrista californiano Gregg Nestor che ebbe occasione di avvicinare il compositore a cui chiese la composizione di una Sonata per chitarra, si sentì opporre un rifiuto. Nestor non si arrese e fece ascoltare al compositore alcuni suoi brani trascritti per chitarra: riuscì a convincerlo. E’ lo stesso Nestor a renderci noto che uno degli ostacoli più difficili di Rózsa fu il timore di sfigurare nel confronto con la Sonata per chitarra (Omaggio a Boccherini) di Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco. Il chitarrista californiano pubblicò quindi una revisione della Sonata di Rózsa (G. Schirmer – Associated Music Puglishers Inc.) e ne eseguì la prima registrazione.

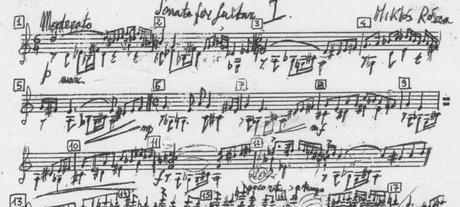

Meno di due anni fa, nella definizione della tracklist di questo progetto discografico, decisi di includere questa preziosa Sonata tra le altre selezionate e inviai un messaggio a Gregg Nestor domandando lui i dettagli del suo lavoro di revisione. Le mie domande erano varie e numerose e con un gesto di grande gentilezza e cortesia fu lo stesso Nestor a mettermi in condizioni di visionare il manoscritto autografo della Sonata del compositore ungherese. Nonostante l’ottimo lavoro di revisione e editing di Gregg Nestor e nonostante la difficile leggibilità del documento inviatomi presi coraggio e dopo alcune settimane di lavoro per la ristrutturazione delle copie del manoscritto, la versione originale della Sonata di Rózsa era nuovamente leggibile.

Costruito su due temi, il primo movimento (“Moderato”) è un esempio da manuale di composizione per chitarra. L’autore fin dalle primissime battute espone il primo tema composto a sua volta da due elementi che si intersecano tra loro e si scambiano vicendevolmente e continuamente i ruoli in una scrittura originalissima e di grande intuizione. Una breve cadenza porta al secondo tema (“Scherzando con spirito”) che appena dopo la sua esposizione cede il passo ad uno sviluppo del primo. L’uso accennato di triadi usate in sequenza e continui richiami a cellule iniziali conducono ad uno sviluppo motivico del secondo tema che stavolta sfocia in un dialogo ritmico serrato per poi riprendere ancora una volta il primo tema sul registro acuto. Il brano si conclude con la ripetizione incrociata del seme tematico che assume diversi significati fino ad dissolversi e diventare nulla.

Il secondo movimento (“Molto moderato, quasi canzone”) esordisce con la melodia cantata nel registro basso della chitarra è supportata da leggeri accordi per poi portarsi su sonorità più acute. Una breve progressione porta ad un febbricitante “più mosso” e animate sequenze si alternano statici segmenti che rimandano ai concetti esposti nel primo tema. Segue un’ampia sezione dove triadi ribattute e costrutti melodici portano alla ripresa che enuncia nuovamente il primo tema ma mostrandone duttilità e estensibilità. L’autore procede dunque ad una meditativa elaborazione del materiale esposto fino ad una evanescente richiamo ritmico che non è altro che un inganno che prelude alla conclusione.

Il terzo movimento (“Allegro frenetico”) è una danza scritta in 4/4 ma che si rivela un incandescente 8/8 dove parti accordali sottolineano gli accenti di una frenetica linea melodica. Strutturalmente e musicalmente è il movimento più semplice mentre da un punto di vista strettamente meccanico si tratta di una vera e propria sfida lanciata all’interprete specie quando il tema viene esposto, nella parte centrale, su due voci. Un vero e proprio turbinio che progredisce per tutta la durata della pagina in un crescendo costante che esplode nei rasgueados e nel “Vivace” finali.

English

English

Born into a middle class family in Hungary, Miklós Rózsa studied music from the earliest years of his life; he studied in Leipzig and perfected his technique with Béla Bartók. His work is very closely linked to the production of Hollywood scores (he won three Oscars) and his chamber and symphonic output covers sixty years.

When Angelo Gilardino wrote to the composer in 1972 asking for a guitar piece, the answer was unfortunately “[…] I would love to accept your proposal, but I really do not feel like writing music for an instrument whose technique I do not know and that I have no time to study […]”. The “prohibition” laid down by Hector Berlioz was still alive. Fifteen years later, Californian guitarist Gregg Nestor also had occasion to approach the composer, asking him to compose a Sonata for guitar, and he also received a refusal. Nestor did not give up and he made the composer listen to some of his pieces transcribed for guitar: he managed to convince him. It is also Nestor who made known that one of the most difficult obstacles of Rózsa was the fear of looking bad in comparison with the Sonata for guitar (Homage to Boccherini) by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco. The Californian guitarist then released a revision of the Sonata by Rózsa (G. Schirmer – Associated Music Publishers Inc.) and the first recording followed.

Less than two years ago, in defining the tracklist of this recording project, I decided to include this valuable Sonata among others selected and I sent a message to Gregg Nestor asking him for details of his work of revision. My questions were many and varied, and with a gesture of great kindness and courtesy, it was the same Nestor who enabled me to view the autograph manuscript of the Sonata by the Hungarian composer. Despite the excellent work of revision and editing by Gregg Nestor, and despite the difficult readability of the document sent to me, I plucked up courage and after a few weeks of work on restructuring the copies of the manuscript, the original version of the Sonata by Rózsa was again readable.

Built on two themes, the first movement (“Moderato”) is a textbook example of composition for guitar. From the very first notes, the author exposes the first theme, in turn composed of two elements that intersect with each other and mutually and continuously exchange roles in a highly original and immensely intuitive score. A brief cadenza leads to the second theme (“Scherzando con spirito”) which, just after its exposure, gives way to a development of the first. The mentioned use of triads in sequence and continual references to the initial cells leads to a motivic development of the second theme that this time results in a tight rhythmic dialogue before resuming once again the first theme on the upper register. The piece ends with the repetition of the crossed repetition of the thematic seed that takes on different meanings until dissolving and becoming nothing.

The second movement (“Molto moderato, quasi canzone”) opens with the melody sung in the lower register of the guitar is supported by light chords and then leading to a more acute sonority. A short progression leads to a feverish “più mosso” and animated sequences alternate with static segments that refer to the concepts presented in the first theme. There follows an extensive section where replayed triads and melodic constructs lead to the recovery that states the first theme again, but showing flexibility and extensibility. The author then proceeds to a meditative elaboration of the material exposed up to an evanescent rhythmic call that is nothing more than a deception which is a prelude to the conclusion.

The third movement (“Allegro frenetico”) is a dance written in 4/4, but that turns out to be a glowing 8/8 where chordal parts highlight the accents of a frantic melodic line. Structurally and musically, it is the simplest movement while, from a strictly mechanical point of view, it is a real challenge for the interpreter, especially when the theme is exposed, in the central part, on two voices. A real swirl that progresses for the duration of the page in a constant crescendo which explodes in the final rasgueados and “Vivace”.

Preview

Preview

Miklós Rózsa (1907 – 1995) – Sonata Op.42 – 3rd Mov.

Cristiano Porqueddu, guitar

from “Novecento Guitar Sonatas” (C) 2014 Brilliant Classics

*Enter your name

*The entered E-mail is invalid.

*2 characters minimum.imagevideolinkDo not change these fields following