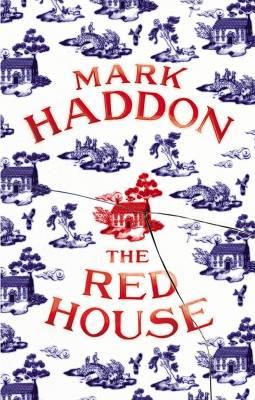

Judging by the book cover, readers of The Red House by Mark Haddon (John Cape, 2012) might anticipate a dark family drama set in the English countryside. Like an old china plate, the book cover is decorated with a pattern of little blue country houses. But there is an ominously red house standing out in the middle of the white and blue porcelain, and the porcelain is cracked (the crack runs through the book cover, you can feel it with your fingers).

Judging by the book cover, readers of The Red House by Mark Haddon (John Cape, 2012) might anticipate a dark family drama set in the English countryside. Like an old china plate, the book cover is decorated with a pattern of little blue country houses. But there is an ominously red house standing out in the middle of the white and blue porcelain, and the porcelain is cracked (the crack runs through the book cover, you can feel it with your fingers).

Indeed The Red House deals with a family (in fact two halves of a family) confined in a country house for a weeklong holiday, so there is plenty of room for drama. However, nothing terrible happens, and little momentous, even though the prelude to the family reunion is a funeral and despite some touches of horror.

The plot is quite simple. The estranged siblings Angela and Richard meet at their mother’s funeral after more than a decade of separation. Now that both their parents are dead, Richard wants to build bridges with his sister, so he invites her, along with her husband Dominic and their children, to spend a week with his own family in a rented house near the Welsh town of Hay-on-Wye. Angela accepts, although she has some resentment towards her younger and more successful brother: Richard was the prodigal son, who kept away from home during his mother’s illness (Alzheimer’s) but could afford to pay for all the hospital bills. The embittered Angela finds irritating even Richard’s second wife Louise and his stepdaughter Melissa, a 16-year-old girl all «sheen and sneer». She thinks they both look like «purchased from an exclusive catalogue at some exorbitant price». Angela’s children are instead less glamorous: Alex, 17, is a prey to his teenage hormones but has a good head on his shoulders; Daisy, 16, and Benjy, 8, are both sensitive, intelligent and much less at ease in the world than their brother. Along with these boys and girls, another mysterious character hovering around the place completes the cast.

The book is about how these people, who barely know each other but are nevertheless related, come to interact in the situation of «forced leisure» of a holiday. It shows the dynamics that develop between young and old - sympathy or indifference, shifting allegiances and misunderstandings – at the same time focusing on their individual worries and little dramas.

Each chapter has the name of a day in the week and describes - with plenty of details – the holiday activities the group engages in. They cook together, go for walks and trips, read, discuss and sometimes argue (duly apologizing afterwards). Minor incidents happen too (some bared-faced flirtation, a couple of unwanted kisses, and a case of near-hypothermia), but they are part of the game.

However, when estranged relatives come together, there is always tension in the air. What’s more, Angela and Richard start digging into the past, making things even worse, because each of them has contrasting memories of the wrongs received and done in their childhood. Like an Alzheimer’s patient, Angela finds herself unable to cope with the tricks of memory and time. It is as if losing her mother, the last custodian of her oldest memories, she had lost a part of her own past.

Despite his efforts, Richard does not really manage to get closer to Angela. In fact, all the adults in the group (except for kindhearted Louisa) seem to share an inability to take a real interest in each other’s problems, or talk about their own feelings. Everybody notices Angela’s depression, but when she tries to broach the subject that obsesses her (the memory of her stillborn girl who, if alive, would be turning eighteen right during the holiday), nobody really listens to her, not even her inert husband Dominic. Angela, on the other hand, is equally insensitive towards her daughter Daisy, who is mired in an identity crisis. Despite all their family trips and shared meals, all the characters seem to be left alone with their problems.

The isolation of the characters, and yet their being together, is reflected in the novel’s structure. The narrative is fragmented into a myriad of short paragraphs, each told from the perspective of a different character, mostly in a stream-of-consciousness technique. It is like a dissonant symphony, with different voices joining in at different times. Snippets from books or newspapers are incorporated into this continuous stream, as well as song titles, brands, and disparate pieces of information (on Nasa rovers or old Chinese legends for example). In short, everything that crosses the eight characters’ mind. Mostly, it is easy for the reader to figure out from whose point of view the story is being told, but at times it can be puzzling. Some musings on the passing of time, on change and permanence, or the solitude of children and adults alike – interspersed in the narrative - could be attributed to an omniscient narrator or perhaps to a common voice, some kind of chorus. Their lyrical tone sharply contrasts with the slang of the dialogue parts. Dialogues, like all quotes from books or music pieces, are printed in italics, a visual device that helps readers navigate through the arsenal of voices in the text.

Haddon’s tricks work well. His language is rich in tones and registers, even though the noun style employed for mimicking the characters’ flow of thoughts may sound at times repetitious. It is a language that makes you gulp down paragraph after paragraph, eager to learn more about the people in The Red House, what they think and how their relationships develop. And you learn a lot about these characters, perhaps too much. A mass of trivial details risks eclipsing the facts that should really matter to the eight holidaymakers. You would expect the inner conflicts tormenting Angela and Daisy to explode, or sharp-edged Melissa to reveal a softer side to her personality, but it does not happen. Instead, besides being repeatedly informed that the food and wine consumed were bought at Marks & Spencer, you get punctilious descriptions of how the men in the family wash frying pans, clean their teeth and go to the bathroom in the early morning, «opening the window afterwards to clear the smell». So the expectations created at the beginning somehow deflate, at the same time as passions and anger in the characters peter out. Like Dominic says, there are no turning points, no revelations, except for a couple of more reactive characters. A seven-day holiday is too short for big things to happen.

Haddon (who used to write for children and became famous in 2003 with The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, a mystery novel told from the point of view of a boy with Asperger Syndrome) portrays the younger ones as more honest and courageous than their parents. He shows how curious they are about the world and its mysteries, how much they enjoy being in nature, feeling part of it (there are beautiful descriptions of landscapes) and the effort they make to come to grips with their lives. Exploring the holiday house, a Romano-British villa with relics of centuries gone by, these young heroes imagine past lives and times, and realize that what once was future has become past. The book’s strength is especially in these young characters and their reactive minds. Haddon makes readers think with them and see with their eyes, discover with them that when your parents let you down, it is time to grow up.

Media: Scegli un punteggio12345 Nessun voto finora