David Keys, giornalista del quotidiano The Indipendent ha firmato un interessante articolo sul tema dei giganti di Monti Prama. Sebbene risulti (forzatamente) approsimativo è decisamente interssante sotto differenti punti di vista. Da non perdere i commenti dei lettori Inglesi in risposta all’articolo pubblicato nello scorso mese di Febbraio (qui il testo orginale). In ultimo vi devo dire che a costo di riportare qualche inesattezza ho provato ad essere puntuale nella traduzione, vogliate perdonarmi per eventuali sviste.

Buona lettura, Andrea.

David Keys.

The Indipendent, Friday 17 February 2012

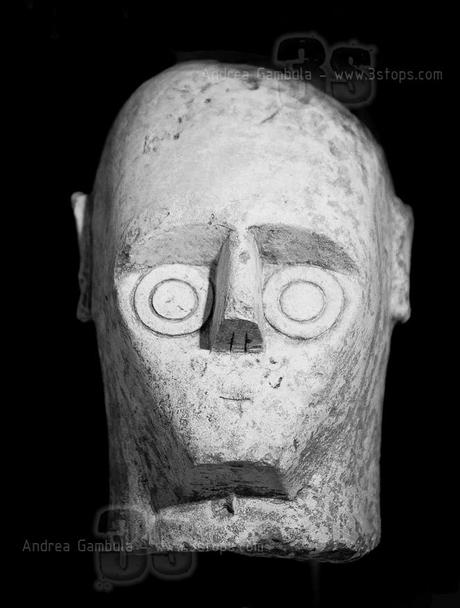

Archeologi e restauratori Sardi hanno faticosamente ricostruito un puzzle costituito da circa 5000 frammenti lapidei ricomponendo un piccolo esercito di guerrieri in pietra delle dimensioni di un uomo. Il piccolo esercito di statue lapidee, unico in Europa, si pensa sia stato distrutto nel bel mezzo del primo millennio ac da parte di un invasore esterno. Sebbene costituito da un numero di elementi molto inferiore rispetto il più famoso esercito di terracotta Cinese quanto ritrovato in Sardegna risulta di grande importanza in quanto più antico di 500 anni oltre che realizzato in pietra (e non in ceramica come quello Cinese).

Otto anni di lavoro hanno reso possibile la ricomposizione di ben 25 dei 33 guerrieri di pietra, rendendo possibile l’identificazione di tre differenti figure scultoree: arcieri, pugilatori e probabilmente dei guerrieri armati di spada.

Originariamente le statue sono state poste alla guardia delle sepolture dell’elite della società caratterizzante la Sardegna dell’età del ferro (VIII sec. a.C.). Non è chiaro se i giganti di pietra sia stati collocati ad eterna protezione del sepolto o a rappresentazione dello stesso.

In epoche successive il sito fu abbandonato e dimenticato, la Sardegna passò dal controllo Cartaginese a quello Romano per poi passare nelle mani dei Vandali, Bizantini, Pisani, Aragonesi, Spagnoli, Austriaci, Savoiardi ed infine, ai giorni nostri, Italiano.

Le migliaia di frammenti furono riscoperti solo nel 1970, la prima campagna di scavo fu condotta nel 1980 da parte dell’archeologo italiano Carlo Tronchetti. Al termine degli scavi fu possibile riassemblare solo due statue mentre la stragrande maggioranza del materiale fu invece conservata presso i magazzini del museo di Cagliari fino al 2004 anno di inizio dell’attività di restauro ad opera del Centro di restauro di Li Punti – Sassari.

Il ricostituito “esercito di pietra Sardo” richiama l’attenzione su una grande civiltà antica, quella Nuragica, della quale non ci conosce ancora molto. La civiltà Nuragica dominò l’isola dal XVI sec. a.C. al VI sec. a.C. e durante il suo periodo di massimo splendore (XVI-XII sec. a.C. ) edificò uno dei monumenti architettonici più imponenti mai prodotti nella preistoria: il nuraghe.

Ancora oggi i resti di circa 7000 fortezze nuragiche – i castelli più antichi d’Europa – continuano a dominare il paesaggio della Sardegna restituendo l’impressione di quanto dovesse apparire eccezionale l’architettura militare dell’età del Bronzo in Sardegna.

Le statue verranno esposte al pubblico a partire dalla prossima estate a Cagliari (località a 100 Km a Sud-est dalla zona di ritrovamento).

Alcune statue raffigurano dei guerrieri armati con archi, altre invece rappresentano delle figure protette da scudi provvisti di un’armatura di protezione ed un elmo con corna sulla testa. Un terzo gruppo di statue rappresentano invece i cosiddetti “pugilatori” ovvero delle figure che stringono uno scudo sopra la testa con la mano sinistra. Quest’ultimi si pensa possano rappresentare gli scudieri posti al servizio dei nobili sepolti nelle tombe hai piedi delle statue stesse.

Oltre i frammenti delle statue è stata rinvenuta una serie di modelli di nuraghe di differente tipologia (monotorre o complessi). E’ probabile che i modelli rappresentano le costruzioni reali monumentali (fortezze dell’Età del Bronzo trasformati in ancestrali dei santuari durante l’età del Ferro) associati con la famiglia immediata di ogni individuo sepolto.

La classe dirigente di questa parte della Sardegna potrebbe essere stato un gruppo relativamente ristretto di individui strettamente correlati. I lavori scientifici effettuati sul materiale scheletrico presso un laboratorio di Firenze suggerisce che la maggior parte degli individui erano imparentati da almeno due generazioni.

Testo di David Keys

Foto Archivio Contusu.it

testo originale:

[Archaeologists and conservation experts on the Italian island of Sardinia have succeeded in re-assembling literally thousands of fragments of smashed sculpture to recreate a small yet unique army of life-size stone warriors which were originally destroyed by enemy action in the middle of the first millennium BC.

It’s the only group of sculpted life-sized warriors ever found in Europe. Though consisting of a much smaller number of figures than China’s famous Terracotta Army, the Sardinia example is 500 years older and is made of stone rather than pottery.

After an eight year conservation and reconstruction program, 25 of the original 33 sculpted stone warriors – archers, shield-holding ‘boxers’ and probable swordsmen – have now been substantially re-assembled.

The warriors were originally sculpted and placed on guard over the graves of elite Iron Age Sardinians, buried in the 8 century BC. The stone guardians are thought to have represented the dead individuals or to have acted as their eternal body-guards and retainers.

However, within a few centuries, the Carthaginians (from what is now Tunisia) invaded Sardinia – and archaeologists suspect that it was they who smashed the stone warriors (and stone models of native fortress shrines) into five thousand fragments. It’s likely that the small sculpted army - and the graves they were guarding - were seen by the invaders as important symbols of indigenous power and status.

The site was abandoned and forgotten. Carthaginian control of Sardinia gave way to Roman, then Vandal, then Byzantine, Pisan, Aragonese, Spanish, Austrian, Savoyard and finally Italian rule.

The thousands of fragments were rediscovered only in the 1970s – and were excavated in the early 1980s by Italian archaeologist Carlo Troncheti. Two of the statues were then re-assembled – but the vast majority of the material was put into a local museum store where it stayed until 2004 when re-assembly work on the fragments was re-started by conservators in Sassari, northern Sardinia.

Sardinia’s newly recreated ‘stone army’ is set to focus attention on one of the world’s least known yet most impressive ancient civilizations – the so-called Nuragic culture which dominated the island from the 16 century BC to the late 6 century BC. Its Bronze Age heyday was in the mid second millennium BC - roughly from the 16 to the 13 century BC, when it constructed some of the most impressive architectural monuments ever produced in prehistory.

Even today, the remains of 7000 Nuragic fortresses (the oldest castles in Europe) still dominate the landscape of Sardinia. Several dozen have stood the test of time exceptionally well – and give an extraordinary impression of what Sardinian Bronze Age military architecture looked like.

The re-assembled stone army is expected to go on display from this summer at southern Sardinia’s Cagliari Museum, 70 miles south-east of the find site, Monte Prama in central Sardinia.

Many of the stone warriors are armed with bows or protected by shields – and wear protective carved stone armour over their chests and horned stone helmet over their heads. Some of the fighters – those believed to portray boxers – carry shields in their left hands, held aloft over their heads. These ‘boxers’ may well have represented or embodied shield-bearers serving the high-ranking members of the Sardinian Iron Age interred in the adjacent graves.

There were also a series of at least ten model Nuragic castles of different designs – some single-towered and others sporting more elaborate ‘multi-tower’ fortifications.

It’s likely that the models represent the actual monumental buildings (Bronze Age fortresses transformed into Iron Age ‘ancestral’ shrines) associated with each buried individual’s immediate family.

The ruling elite of this part of Sardinia may well have been a relatively tightly knit group of closely related individuals. For scientific work carried out on the skeletal material at a laboratory in Florence, suggests that most of the dead individuals were from just two generations of a single extended family.]